Here’s a simple thing you can do to help you focus better and improve your study sessions . . .

Take regular exercise breaks.

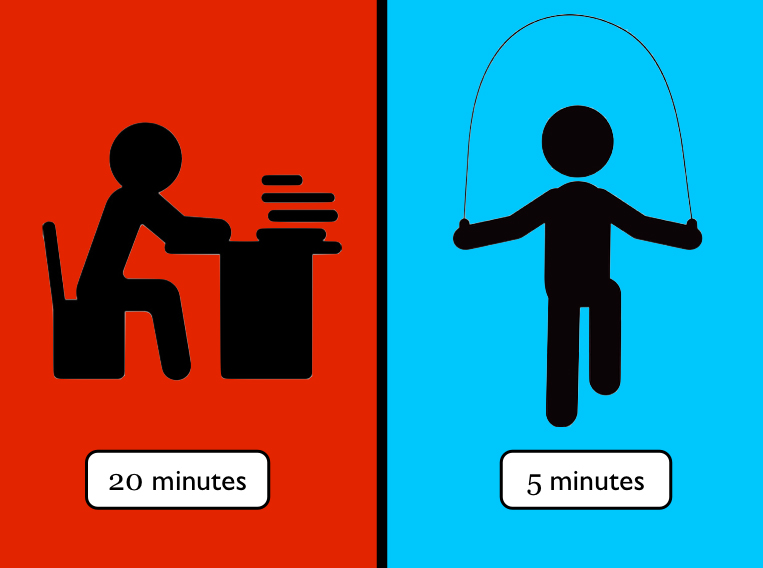

A study titled Sweat so you don’t forget found that engaging in regular five minute exercise breaks reduced mind wandering, improved focus, and enhanced learning.

In this study the researchers wanted to know if engaging in short exercise breaks could help with learning.

They took a group of 75 psychology students and split them into three groups.

Group 1: Exercise breaks group

Group 2: Non-exercise breaks group

Group 3: No breaks group

All the students had to watch the same 50 minute psychology lecture. But the difference between the groups was this . . .

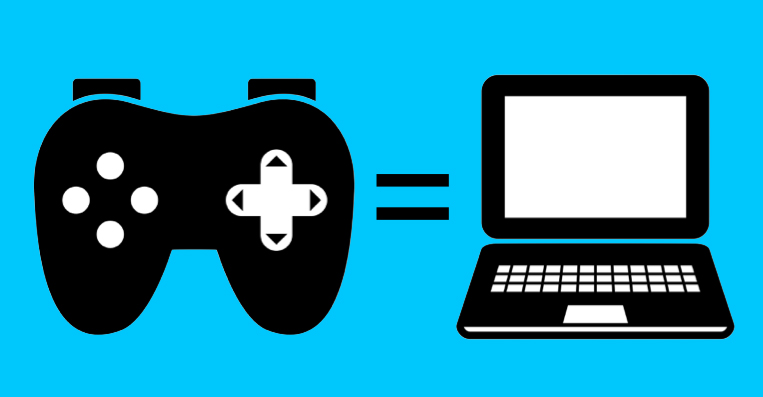

The exercise breaks group performed five minutes of exercise every 17 minutes. The non-exercise breaks group played a simple video game for five minutes every 17 minutes. The no breaks group had to watch the entire lecture without getting a single break.

The students in the exercise breaks group could focus better and they retained more information. They also found the lecturer easier to understand.

The researchers said:

“The exercise breaks buffered against declines in attention resulting in superior engagement during the latter part of the lecture compared to the other two groups.”

One would think they would show some improvements in attention and memory since they were getting breaks. But they didn’t show any significant improvements.

In fact, they performed just as well as the no breaks group in terms of attention and memory.

The researchers concluded:

“One possibility is that the computer game played during the non-exercise break may have acted as a second cognitive task as opposed to a cognitive break. Switching between two cognitive tasks can deplete attention and impair performance for both tasks.”

This shows the type of activity you engage in on a study break is really important. It pays to get out of your head and move your body!

It was a series of exercises performed for 50 seconds each followed by a rest break:

1) Jumping jacks (50 seconds) + Rest (10 seconds)

2) Heeltaps (50 seconds) + Rest (10 seconds)

3) High knees (50 seconds) + Rest (10 seconds)

4) Split jumps (50 seconds) + Rest (10 seconds)

5) Hamstring kickers (50 seconds) = The End

Since reading this study, I’ve started to incorporate more exercise breaks into my day and I’m noticing a big difference.

Personally, I’m not a fan of some of the exercises the researchers made the participants do in this study. So, I have replaced them with other cardio exercises I enjoy doing, such as punching a boxing bag and using a skipping rope.

I also find doing 50 seconds of non stop exercise pretty exhausting. For this reason, I’ve reduced my exercise time down to 40 seconds followed by a 20 second rest break. I find it helps to time my exercise sprints/rest breaks using an interval timer on my phone instead of a kitchen timer (which can feel a little clunky).

Feel free to experiment with different exercise/rest ratios. Make it work for you. As your fitness levels improve, you can increase the period of time you exercise for.

After working for 20 or 30 minutes, get up and take a five minute exercise break.

You don’t have to do jumping jacks or hamstring kickers. Select simple exercises you want to do.

Notice how you feel before and after your exercise break.

After experimenting with this simple strategy, I can say with confidence that I feel more energised and mentally sharper throughout the day. Try it and let me know how you go!

Share This:

But I’ve also had to learn to move to learn.

Does that makes sense? If not, let me explain myself.

Like most students, I was conditioned to sit still in a chair for hours each day. Even though I felt chained to my chair in school, there was one part of my body that I could move: my arms and hands.

I could gesture to express ideas.

Being half Italian, using my hands to gesticulate feels completely natural and normal. Growing up, I watched my Italian relatives gesture dramatically to stress a point and communicate ideas.

Having been exposed to this from a young age, I didn’t know how to behave any differently. It’s just what you did when you spoke: you used your hands.

However, my bold hand gestures weren’t always welcome, and they inevitably drew attention in the classroom.

People would comment, “Ha! Look at the way she uses her hands!” and “You’re so Italian!”.

My hand gestures were too over-the-top. I needed to tone things down.

When I was in Year 9, I tried to restrain my hand gestures. I alternated between sitting on my hands, folding them and cupping them in my lap.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but by suppressing my hands’ natural urge to move, I was doing my brain a disservice.

This study by Langhanns and Müller found that when students were asked to sit still while solving problems, their cognitive load increased and their overall success in solving problems decreased.

In other words, when you focus on being still and try to ignore your body’s natural urge to move, this consumes a lot of your brainpower.

Fortunately, I gave up trying to suppress my hand gestures. There was no point in trying. My hand gestures were like a wild horse. They would always break free.

All these years later, I can see that my ability to gesture naturally and effortlessly made me good at public speaking. While other robotic speakers had to be coached into adding a few hand gestures, I moved my hands with ease.

But that’s not all; by using my hands in class, I was also tapping into special learning superpowers.

Research shows physical movement, including the use of gestures, helps improve understanding and boosts memory.

I’m referring to an experimental study conducted by a husband and wife research team, Tony and Helga Noice. This couple spent many years studying actors and their ability to learn and recall lines.

Their research found that actors were able to accurately recall lines that had been accompanied by movements months after the final stage performance. However, these same actors struggled to remember lines that had been spoken when they remained in one place.

The Noices wanted to know if ordinary people (non-actors) could benefit from engaging in physical movement and using gestures when learning and retrieving dialogue.

They devised an experiment involving 23 university students. They split these students into three groups:

Group 1: Movement condition

Group 2: Verbal communication only condition

Group 3: Memorisation condition (Control)

In the movement condition, students were taught how to move in the scene (without reading their scripts). They were then given scripts and read their lines while moving their bodies.

In the verbal communication condition, these students sat on chairs and were told to read their lines out loud. They weren’t allowed to move.

Groups 1 and 2 were told not to memorise the dialogue but instead to focus on the meaning of what they were saying. They were instructed to adopt an actor’s approach to learning (i.e., to be fully present and mean what they were saying as they said it).

In contrast, Group 3 (the control group) was instructed to try to memorise their lines using whatever strategy they’d found successful in the past.

Students in each group were given only five minutes to learn their lines. They were then given a brief distractor task (“Write down five movies you saw recently”) before being tested on their ability to recall their lines.

The researchers found that the students in the movement condition remembered 76% of their lines compared with only 37% for the memorisation control group.

The researchers concluded:

“Students who actively experienced communicating the meaning of the material by using both words and movements recalled significantly more material than did either students who communicated using only words or students who deliberately memorized the same text.”

It’s important to note that the students in the movement condition weren’t just waving their arms around in the air. Their movements had meaning and were connected to what they were saying.

There are several ways you can utilise your body to learn.

If you’re trying to learn a new concept or memorise a presentation, don’t be afraid to use your hands and body. Think about what you’re saying. Can you apply a gesture or move your body to help you memorise an idea and improve your understanding?

As the authors of The Extended Mind In Action state:

“…the feel of our hands making a gesture reinforces our memory.”

This is why I also practice my presentations on my feet, using my hands and all my body to express ideas.

If you’re an online educator or teacher, it’s really important that students can see your arms and hands. Research shows that instructional videos that include people gesturing result in significantly more learning for people who watch them.

When I first started delivering online presentations, I made the mistake of only showing my head and shoulders.

After exploring the research in this area, I quickly adjusted my studio setup so that students could see my hands and arms as well. This small tweak made a huge difference in improving student learning.

I also encourage students to gesture back to check their understanding and reinforce key ideas. If you’re a teacher, I encourage you to try doing this with your students, too.

Besides using specific gestures and movements to learn concepts and dialogue, it’s also worth considering the benefits of engaging in light to moderate-intensity exercise before sitting down to study.

A fabulous research study called Sweat So You Don’t Forget found that when students engaged in five-minute exercise breaks every 17 minutes, they could focus better and remembered more than students who didn’t get any breaks or had a sedentary break (playing video games).

Annie Murphy Paul writes in her book The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain:

“…we have it within our power to induce in ourselves a state that is ideal for learning, creating, and engaging in other kinds of complex cognition: by exercising briskly just before we do so.”

This is why, every morning, before I start my work, I run on my treadmill or ride my stationary bike for at least 20 minutes. This gives me a cognitive boost: it improves my focus, creativity, executive function and ability to learn.

The movement also helps to decrease anxiety by supplying my brain with a dose of BDNF (i.e. brain-derived neutrophic factor). Dr Jennifer Heisz, in her book Move the Body, Heal the Mind, explains that BDNF is like fertiliser for the brain. She writes:

“BDNF acts like a fertilizer that promotes the growth, function, and survival of brain cells, including those that turn off the stress response.”

She continues:

“Immediately after exercising, our brain cells are bathed in BDNF, which protects those cells against the toxic effects of high stress.”

As I think back to high stress times in my life, I have no doubt that movement (and regular doses of BDNF) are what got me through these periods.

Your body is a powerful tool to help you learn. The research is clear that moving your body enhances your ability to think and learn.

It’s time to move past the outdated idea that learning means sitting still and being serious. It costs us nothing to gesture with our hands while reading about a concept or to go for a walk outside before studying.

Movement benefits us in many ways, so why not include some in your study routine today?

While I always kept an eye on the amount of petrol in the tank, I also needed to pay close attention to my own personal energy levels.

It was important to avoid pushing myself past empty and depleting my energy reserves because if I did, I would end up feeling emotionally wrecked.

I clearly remember one day when I pushed myself too hard. Looking back, it seems comical now. But I wasn’t laughing at the time.

It was my 24th birthday. I had woken up that morning with great intentions, thinking “It’s my birthday! Let’s make it a great day!”

I was trying too hard to make it a “great day”. I was forcing it, and perhaps that’s partly why everything went pear-shaped. Here’s what happened . . .

I had a school presentation later that day, so I spent the morning preparing for it before driving over an hour to deliver the presentation.

The time slot for the talk wasn’t ideal—my talk was scheduled for the last period on a Friday afternoon—but I was thinking, “Hey! It’s my birthday. Let’s make it a great day!”

What can I say?

The session didn’t go well.

There were IT issues and the students’ minds were elsewhere. But you couldn’t blame the students. They were tired and I was the only thing standing between them and the weekend.

When I wrapped up the session, I felt tired and hungry.

But I foolishly ignored my body’s needs. On an empty stomach, I began the long drive home. I was desperate to get back and be in my own space.

Within 10 minutes, I found myself stuck in peak-hour traffic. But I wasn’t just stuck in traffic; I was also stuck in an anxiety loop.

Psychologist Risa Williams explains an anxiety loop as “a negative thought cycle that makes you feel stuck in a rut”. You can’t rationalise your way out of an anxiety loop. Logic doesn’t cut it.

I kept thinking about how the talk could have gone better, why my birthday had been such a flop . . . these annoying tunes kept playing over and over in my mind and they kept getting louder and louder.

I was about halfway home when something unexpected happened: I began sobbing uncontrollably behind the wheel of my car. I just felt incredibly sad.

I realised it was dangerous to drive while crying, so I pulled over and called my mum.

My mum and I would chat on the phone most days, but I remember this conversation especially well because my mum didn’t pull any punches.

Mum: What’s wrong Jane? Why are you upset?

Me: It’s my birthday and I wanted to have a great day but I just feel so awful. Everything has gone wrong today. The day has been a total flop.

Mum: Jane, have you had anything to eat?

Me: No.

Mum: You’re hungry! I know what you’re like when you’re hungry. You need to find a place to eat.

Me: But there’s nothing healthy to eat around here . . . there are no healthy options.

Mum: I don’t care. Order something. Anything. You need to eat. Go do that right now!

I found a café that was still open (it was 3:30pm) and ordered a burger from the menu.

When the burger came out 10 minutes later, I felt emotionally wrecked.

But after eating that big, juicy burger, I felt instantly better.

The world now felt like a new and different place. I had strength again. With tear-free eyes, a calm mind, and more energy in my system, I got in my car and drove myself home safely.

That experience taught me an important lesson. I learnt I had to stop pushing myself past the point of empty (something I’d done far too often for too many years).

I had to start listening to my body and the signals it was sending me.

Feeling hungry? Have a healthy snack.

Tired? Take a quick nap.

Thirsty? Have a few sips of water.

Sitting for too long and in pain? Get up and move.

Eyes and brain hurting from staring at a screen for too long? Take a break and look out the window.

It also taught me how engaging in small behaviours (tiny habits) can significantly impact how you think and feel.

All of these habits are designed to boost and conserve my energy. That’s the great thing about habits: they conserve your energy by automating your behaviour and combating decision fatigue. As Kevin Kelly states in his book Excellent Advice for Living:

“The purpose of a habit is to remove that action from self-negotiation. You no longer expend energy deciding whether to do it. You just do it.”

These 15 tiny habits are so deeply ingrained that I do all of them most days. I don’t waste time and energy thinking, “Should I go on the treadmill or stay in bed and read a book?” or “Do I do my gratitude practice or eat breakfast?” I have established a routine of healthy behaviours that work for me.

These tiny habits don’t take long to do, and best of all, they stop me from running out of energy and crashing. I also haven’t been sick in over three years (mainly due to Habit #13: Wearing a n95 mask).

You might be wondering why I’m still wearing a mask when covid restrictions have eased. There are a few reasons: I know several people with long covid (and they are suffering). Their quality of life is not what it once was.

I’ve also read a lot of the research on covid. Research shows covid can cause significant changes in brain structure and function.

This study found that people who had a mild covid infection showed cognitive decline equivalent to a three-point loss in IQ and reinfection resulted in an additional two-point loss in IQ.

Other studies have found covid can disrupt the blood brain barrier and cause inflammation of the brain. Since I rely on my brain to do everything, wearing a n95 mask (not a cloth or surgical mask) is a simple and effective habit I’m happy to keep up to protect my brain and body.

At the end of the day, cultivating healthy habits is about noticing the little (and big) things that make a difference and then experimenting with those things.

For example, Habit #3 (Moving on a treadmill first thing every morning) came about when I noticed the dramatic difference in how I felt on the days I ran on the treadmill compared to the days I didn’t (I felt mildly depressed on the days when I didn’t go for a run).

Habit #4 emerged after I noticed that eating a particular breakfast (overnight oats with berries) made me feel amazingly good compared to having a smoothie or a bowl of processed cereal for breakfast (which would spike my blood sugar levels).

Your health influences everything in life—and I mean absolutely everything. It influences how you interact with the people in your life, how well you learn and focus, your energy levels, and how you do your work.

As Robin Sharma explains in his book The Wealth Money Can’t Buy, health is a form of wealth.

Sharma writes:

“If you don’t feel good physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually, all the money, possessions and fame in the world mean nothing. Lose your wellness (which I pray you never will) and I promise you that you’ll spend the rest of your days trying to get it back.”

One way you can build your wealth is by cultivating tiny healthy habits.

As I think back to my younger self, 24 years old and ignoring the warning signs my body was sending me, I can’t help but feel a bit embarrassed. But as Kevin Kelly says, “If you are not embarrassed by your past self, you have probably not grown up”.

I’ve grown up a lot. I’ve come to realise developing awareness and taking time out to step back and reflect are critical to living a healthy, grounded life. When you notice what makes you feel good and not so good, you can make tiny tweaks to improve your life.

If you aim to do more of the things that leave you feeling good and less of the things that leave you feeling depleted and fatigued, you can’t really go wrong.

In the words of Psychologist Dr Faith Harper, “Keeping our brains healthy and holding centre is a radical act of self-care”.

On that note, take a moment to check in with your body. What does it need right now? Could you do something small to treat your body and mind with a little more care? Step away from the screen and do it now.

I didn’t know how to relax. I had one speed and one speed only . . . GO!

When I started dating my husband, he made a comment I never forgot. He said, “You’re intense.”

I laughed it off, thinking, “How ridiculous!”. But looking back, he was right.

Over the last few years, I’ve learnt to live life at multiple speeds and different intensities.

I’ve also learnt how to manage my energy better and pace myself. One thing the pandemic taught me was the importance of slowing down and taking regenerative breaks.

For many years, even though I intellectually understood the importance of rest, I struggled to do it.

For some reason, I thought I had to be always working.

My to-do list was something I had to power through. One thing after another. Got that thing done? Quick! Cross it off the list! Onto the next task.

As a student, I developed a bad habit of staying back late at university. As an undergrad, I’d hang out with my psychology friends in the computer labs until nearly midnight (I had to call the university security service to escort me to my car!).

Then, as a PhD student, I’d be in my office working late when everyone else had gone home. I’d buy takeaway that I’d eat alone at my desk. I’d get home late. I’d get to bed late.

How did I feel the next day?

Not great.

The problem with this approach is now glaringly obvious to me: because I was getting less sleep, I started to feel run down, which made it hard for me to focus, do my best thinking, and work efficiently.

Going fast all the time was actually slowing me down.

Then, I met a Brazilian PhD student called Carlos.

Carlos showed me there was a different way to work. A better way. A more sustainable way.

When I first met Carlos, I was taken aback by his beaming smile and infectious laugh.

He seemed genuinely happy, which wasn’t the case for many PhD students.

It wasn’t uncommon to see PhD students glued to their seats for hours with a 2-litre bottle of Coke on their desks. But this was not Carlos’s style.

I learnt that Carlos rode his bike to university every day (partly to save money and partly to clear his mind). He’d take breaks to play soccer and go rock climbing.

With all this activity, you might be wondering whether Carlos was managing to get any work done on his PhD.

He certainly was.

Carlos was super productive as a PhD student.

He was publishing papers and on track to finish his PhD on time, all with a big smile.

Here’s the really interesting thing about Carlos . . .

When he started working on his PhD, he was like me: pushing himself to work long, ridiculous hours.

As an International student, Carlos had a strict deadline for submitting his PhD thesis. At the beginning of his PhD, he told me he was driven by fear that he might not finish the work in time, so working nonstop seemed like the only path forward.

But then Carlos had an epiphany.

He realised he was just as productive when he allowed himself to engage in fun activities (e.g., rock climbing and playing soccer) as when he insisted on pushing himself to work crazy hours without taking any breaks.

This made Carlos realise that he needed to get serious about these fun rest breaks and prioritise them.

Whether Carlos realised it or not, he was emulating the behaviour of top research scientists.

In one longitudinal study, 40 scientists in their 40s were followed for 30 years. These scientists had attended top universities and showed promise in their careers.

The researchers wanted to know the difference between the people who had become top scientists and those who became mediocre scientists.

In other words, what were the top scientists doing that the mediocre scientists weren’t doing?

One of the key differences that stood out was movement.

The top scientists moved a lot more than the mediocre scientists. They engaged in activities such as skiing, hiking, swimming, surfing and playing tennis.

In contrast, the mediocre scientists did a lot less physical activity.

They were more likely to say, “I’m too busy to go hiking this weekend. There’s work I need to catch up on.” They saw physical movement as eating into the time they could be working.

The top scientists thought differently about movement. Moving their bodies was critical to doing good scientific work. It was something they needed to prioritise in their lives.

When I first read about this study, I immediately thought about Carlos. Riding his bike, playing soccer, and rock climbing were all activities that helped him work effectively on his PhD. These weren’t time-wasting activities; they were necessities.

Movement gets you out of your head and grounds you in your body. It also gives you space away from your work, which our minds need when doing complex and challenging tasks.

In addition, as you move your body, your brain is bathed in feel-good chemicals. It’s easier to get things done when you feel good and less stressed. You can have more fun. You come back into balance.

But do all breaks need to involve movement?

Not always. But you should try to find fun activities that you can do away from your desk, phone, or computer.

Do something that lets your mind loose and requires little to no mental effort to execute.

Here are some of my favourite fun break activities:

These fun break activities may not seem like much fun to you. I understand if steaming your clothes sounds boring (I’m even surprised by how much fun this is).

Your job is to discover your own fun break activities. But how do you do this? It’s simple – you follow the Rules of Fun.

Psychologist Risa Williams lays out the Rules of Fun in her brilliant book The Ultimate Anxiety Toolkit.

The Rules of Fun are as follows:

What was fun for you yesterday may not be fun today. That’s okay. Focus on what you find fun today. Only you know what that is.

The activity isn’t something you should find fun. It’s actually fun for you (it brings a smile to your face and a sense of calm).

For example, many Australians love watching the footy, but I don’t enjoy it. I’d much rather head outside, run around, kick a footy, or throw a frisbee. This is fun for me!

Risa Williams also points out that your list of fun activities will need to be updated regularly. She explains that we are constantly changing and evolving, so naturally, what we find fun will change and evolve, too.

Stay flexible and trust your intuition when it comes to the activities you find fun.

Start to listen to your body. Begin to notice what activities leave you feeling good.

The break activity shouldn’t leave you feeling mentally fried or emotionally wrecked. If it does, you’ve violated this rule.

For example, I never feel good when binge-watching a Netflix series or sitting for long periods. In contrast, I nearly always feel good after a walk.

As I mentioned, you need to get out of your head and get grounded in your body.

If you’re stuck in an anxiety loop about a comment or post a friend made on social media, the last thing you want to do is go online. You need to calm down by engaging in a fun activity (away from screens) that brings you back into balance.

You don’t need to fly to Bali or have an expensive massage to take a fun break. You can engage in many free and cheap activities at home and on your own.

Going for a walk around the block is free and easy. Drawing some silly faces on a scrap of paper is free and fun.

In contrast, travelling to the gym to take a cardio class (and getting there on time) feels much harder.

Let’s face it: if the break activity feels difficult or requires a lot of mental or physical effort, time, or money, you’re probably not going to do it.

However, when your fun break activities are easy, you’re more likely to do them again and again.

Little kids know how to have fun. They will happily and instinctively pick up some crayons to draw. They’ll nap without guilt. But as we grow older, many of us lose our sense of fun and our ability to rest. We start to take ourselves too seriously.

But no matter your age, it’s time to get serious about taking fun breaks.

I’ve discovered that the key to feeling satisfied and content is to feel calm and grounded. But you can’t feel calm and grounded if you constantly push yourself to do more and more.

To keep your body and mind in balance, you need to insert fun breaks into your day. These fun breaks are not a waste of time. They are essential for feeling good, fully alive, and doing your best work.

So, in the spirit of fun, what will you do to give yourself a fun break? Follow the rules of fun and experiment with different activities. Be playful!

Finally, do you know what happened to Carlos? He’s gone on to become a respected Senior Lecturer at a top university in Australia . . . and he still enjoys going rock climbing.

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive and engaging study skills sessions for Australian secondary schools. She has worked with thousands of secondary students, parents, teachers and lifelong learners over the past 15 years.

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to Dr Jane’s newsletter:

© 2025 Learning Fundamentals