It had been an intense year of work and study. I desperately needed a break.

So I packed a backpack and went hiking with a group of friends. We did the sorts of things you see people do in wilderness films: we swam in rivers, slept under the stars, and ate the simplest of meals.

Five days later, I re-emerged from the forest feeling re-energised and with a new perspective. I felt excited about life again.

If you’ve ever skipped a holiday or used your holidays to catch up on work, you know at some level this is bad for your soul.

Research shows people who skip holidays are more likely to:

• suffer from burnout;

• feel emotionally exhausted;

• be less productive;

• have trouble concentrating during their free time after work; and

• find it harder to deal with the challenges of work, study, and life.

Think of the last time you felt really exhausted. How easy was it for you to do your work?

With a tired mind, it’s hard to get anything done. You can’t do your best work.

Let’s face it . . .

You’re not a machine.

You’re a human being.

Your energy is finite.

You have limits.

Following any period of intense or stressful work, you need to rest and recover.

If you choose to ignore your biological limits and burn yourself out, it can take 12 months to fully recover. It’s your choice. Your call. Personally, I wouldn’t risk it.

So it’s time to get serious about rest and in particular, holidays.

Let’s take a quick look at the science . . .

Research by Sabine Sonnentag and her team found we need to experience the following four things to fully recover from stress:

1) Relaxation;

2) Mental detachment from work;

3) A sense of being in control; and

4) Mastery experiences.

In his book Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less, Alex Soojung-Kim Pang encourages us to think of breaks as being like meals. You want your meal (i.e. your break) to be nourishing, so it needs to be high in all four of the components listed above.

The good news is you can train yourself to get better at doing these four things. It just takes practice.

Below we explore each of these factors in more detail. Read on!

This is about calming your mind and body.

What’s the best way to relax?

There are no hard and fast rules but you could try:

• Meditating;

• Having a massage;

• Listening to relaxing music;

• Spending time in nature;

• Doing yoga;

• Breathing exercises; and

• Taking a long hot bath.

What do these activities have in common?

They require very little effort. And they make you feel good!

Research by Frederickson (2001) found that when people feel good (i.e. they experience positive emotions) this helps to boost their energy levels.

Have you ever found yourself worrying about school/work when you weren’t at school/work?

When you do this, you’re wasting your precious (and finite) mental energy. But what’s even worse is that no recovery can occur when you worry.

One study by Sonnentag, Binnewies and Mojza (2008) found that low psychological detachment from work in the evening is associated with feeling exhausted and tired in the morning.

Want to wake up feeling refreshed and alert? Then stop any negative thoughts about work and school as soon as you get home.

Easier said than done, right?

Again, it’s just practice.

Here are some strategies that help me to switch off from my work/study:

• Set a worry time (worry o’clock): Find yourself worrying? Quickly jot down the thought that is bothering you. Then tell yourself you’ll revisit that thought later at worry o’clock.

• Create non-work zones in your room/home: Deliberately segment work and off-work life. Don’t bring any work into your non-work areas.

• Don’t do any work on your holidays: Put your books and notes away. Your top priority is to have fun, relax and engage in mastery experiences (see point 4 below).

• Get moving: Engaging in intense physical exercise can provide ‘time out’ from worrisome thoughts. When I exercise, my focus is just on doing each movement (nothing else). I tune into how my body feels. Increased levels of endorphins, serotonin, and dopamine following exercise also help with the recovery process.

Do you feel in control of your time when you’re not at school or work? Can you engage in activities that you enjoy and find meaningful?

If the answer is no, you need to work on feeling more in charge of your life.

Here are some questions to consider:

• Are you overscheduled?

• Could you cut back on a few activities/commitments to free up more time for fun and relaxation?

• Can you outsource any activities?

• Can you do certain activities more efficiently to free up more time?

• Can you reduce time confetti in your life?

These are experiences that challenge and stretch you in some way. When you engage in them, you tend to forget about your work and/or school.

These activities require you to exert a bit of effort, but you don’t want them to leave you feeling completely exhausted.

Here are some examples of mastery experiences:

• Physical exercise;

• Learning a new instrument (e.g. the piano);

• Learning a foreign language;

• Volunteering in the community; and

• Taking a free online course on a topic that interests you.

As a general rule of thumb, try to limit time on digital devices over the holidays.

Let me be clear: technology can be a great tool to help you engage in a mastery experiences. But depending on how you use it, it can also inhibit the recovery process.

Screen time leisure activities, such as scrolling on your phone and watching Netflix, don’t really challenge us. We typically sit down and enter a passive, zombified state. This in turn can lead to boredom, apathy and depression.

For every hour you spend in front of a screen, that’s an hour you could have spent at the beach, going for a walk in nature, working on a creative project or learning how to cook a new dish.

Here’s another reason to limit your screen time . . .

If you’re looking at a screen 30 minutes before going to bed, you’re messing with your melatonin (a hormone that makes you feel sleepy). The light emitted from screens has been shown to suppress the production of melatonin, thereby making it harder for people to fall asleep.

Scrolling through your social media feed so close to bedtime also means you’re at risk of seeing content that upsets you.

Put simply . . .

As Demerouti and her team state:

“The better an individual’s physiological and psychological state before bedtime, the longer and better the quality of sleep she/he will have. A better quality and quantity of sleep in turn leads to a better psychological and energetic state the next morning before going to work.”

So put your phone to bed at least 30 minutes before you plan on going to bed. This simple action could change both your mood and outlook in dramatic and profound ways.

For these holidays, I encourage to explore and experiment with different ways to make your break truly restorative. And most importantly, make sleep your top priority.

Share This:

I didn’t know how to relax. I had one speed and one speed only . . . GO!

When I started dating my husband, he made a comment I never forgot. He said, “You’re intense.”

I laughed it off, thinking, “How ridiculous!”. But looking back, he was right.

Over the last few years, I’ve learnt to live life at multiple speeds and different intensities.

I’ve also learnt how to manage my energy better and pace myself. One thing the pandemic taught me was the importance of slowing down and taking regenerative breaks.

For many years, even though I intellectually understood the importance of rest, I struggled to do it.

For some reason, I thought I had to be always working.

My to-do list was something I had to power through. One thing after another. Got that thing done? Quick! Cross it off the list! Onto the next task.

As a student, I developed a bad habit of staying back late at university. As an undergrad, I’d hang out with my psychology friends in the computer labs until nearly midnight (I had to call the university security service to escort me to my car!).

Then, as a PhD student, I’d be in my office working late when everyone else had gone home. I’d buy takeaway that I’d eat alone at my desk. I’d get home late. I’d get to bed late.

How did I feel the next day?

Not great.

The problem with this approach is now glaringly obvious to me: because I was getting less sleep, I started to feel run down, which made it hard for me to focus, do my best thinking, and work efficiently.

Going fast all the time was actually slowing me down.

Then, I met a Brazilian PhD student called Carlos.

Carlos showed me there was a different way to work. A better way. A more sustainable way.

When I first met Carlos, I was taken aback by his beaming smile and infectious laugh.

He seemed genuinely happy, which wasn’t the case for many PhD students.

It wasn’t uncommon to see PhD students glued to their seats for hours with a 2-litre bottle of Coke on their desks. But this was not Carlos’s style.

I learnt that Carlos rode his bike to university every day (partly to save money and partly to clear his mind). He’d take breaks to play soccer and go rock climbing.

With all this activity, you might be wondering whether Carlos was managing to get any work done on his PhD.

He certainly was.

Carlos was super productive as a PhD student.

He was publishing papers and on track to finish his PhD on time, all with a big smile.

Here’s the really interesting thing about Carlos . . .

When he started working on his PhD, he was like me: pushing himself to work long, ridiculous hours.

As an International student, Carlos had a strict deadline for submitting his PhD thesis. At the beginning of his PhD, he told me he was driven by fear that he might not finish the work in time, so working nonstop seemed like the only path forward.

But then Carlos had an epiphany.

He realised he was just as productive when he allowed himself to engage in fun activities (e.g., rock climbing and playing soccer) as when he insisted on pushing himself to work crazy hours without taking any breaks.

This made Carlos realise that he needed to get serious about these fun rest breaks and prioritise them.

Whether Carlos realised it or not, he was emulating the behaviour of top research scientists.

In one longitudinal study, 40 scientists in their 40s were followed for 30 years. These scientists had attended top universities and showed promise in their careers.

The researchers wanted to know the difference between the people who had become top scientists and those who became mediocre scientists.

In other words, what were the top scientists doing that the mediocre scientists weren’t doing?

One of the key differences that stood out was movement.

The top scientists moved a lot more than the mediocre scientists. They engaged in activities such as skiing, hiking, swimming, surfing and playing tennis.

In contrast, the mediocre scientists did a lot less physical activity.

They were more likely to say, “I’m too busy to go hiking this weekend. There’s work I need to catch up on.” They saw physical movement as eating into the time they could be working.

The top scientists thought differently about movement. Moving their bodies was critical to doing good scientific work. It was something they needed to prioritise in their lives.

When I first read about this study, I immediately thought about Carlos. Riding his bike, playing soccer, and rock climbing were all activities that helped him work effectively on his PhD. These weren’t time-wasting activities; they were necessities.

Movement gets you out of your head and grounds you in your body. It also gives you space away from your work, which our minds need when doing complex and challenging tasks.

In addition, as you move your body, your brain is bathed in feel-good chemicals. It’s easier to get things done when you feel good and less stressed. You can have more fun. You come back into balance.

But do all breaks need to involve movement?

Not always. But you should try to find fun activities that you can do away from your desk, phone, or computer.

Do something that lets your mind loose and requires little to no mental effort to execute.

Here are some of my favourite fun break activities:

These fun break activities may not seem like much fun to you. I understand if steaming your clothes sounds boring (I’m even surprised by how much fun this is).

Your job is to discover your own fun break activities. But how do you do this? It’s simple – you follow the Rules of Fun.

Psychologist Risa Williams lays out the Rules of Fun in her brilliant book The Ultimate Anxiety Toolkit.

The Rules of Fun are as follows:

What was fun for you yesterday may not be fun today. That’s okay. Focus on what you find fun today. Only you know what that is.

The activity isn’t something you should find fun. It’s actually fun for you (it brings a smile to your face and a sense of calm).

For example, many Australians love watching the footy, but I don’t enjoy it. I’d much rather head outside, run around, kick a footy, or throw a frisbee. This is fun for me!

Risa Williams also points out that your list of fun activities will need to be updated regularly. She explains that we are constantly changing and evolving, so naturally, what we find fun will change and evolve, too.

Stay flexible and trust your intuition when it comes to the activities you find fun.

Start to listen to your body. Begin to notice what activities leave you feeling good.

The break activity shouldn’t leave you feeling mentally fried or emotionally wrecked. If it does, you’ve violated this rule.

For example, I never feel good when binge-watching a Netflix series or sitting for long periods. In contrast, I nearly always feel good after a walk.

As I mentioned, you need to get out of your head and get grounded in your body.

If you’re stuck in an anxiety loop about a comment or post a friend made on social media, the last thing you want to do is go online. You need to calm down by engaging in a fun activity (away from screens) that brings you back into balance.

You don’t need to fly to Bali or have an expensive massage to take a fun break. You can engage in many free and cheap activities at home and on your own.

Going for a walk around the block is free and easy. Drawing some silly faces on a scrap of paper is free and fun.

In contrast, travelling to the gym to take a cardio class (and getting there on time) feels much harder.

Let’s face it: if the break activity feels difficult or requires a lot of mental or physical effort, time, or money, you’re probably not going to do it.

However, when your fun break activities are easy, you’re more likely to do them again and again.

Little kids know how to have fun. They will happily and instinctively pick up some crayons to draw. They’ll nap without guilt. But as we grow older, many of us lose our sense of fun and our ability to rest. We start to take ourselves too seriously.

But no matter your age, it’s time to get serious about taking fun breaks.

I’ve discovered that the key to feeling satisfied and content is to feel calm and grounded. But you can’t feel calm and grounded if you constantly push yourself to do more and more.

To keep your body and mind in balance, you need to insert fun breaks into your day. These fun breaks are not a waste of time. They are essential for feeling good, fully alive, and doing your best work.

So, in the spirit of fun, what will you do to give yourself a fun break? Follow the rules of fun and experiment with different activities. Be playful!

Finally, do you know what happened to Carlos? He’s gone on to become a respected Senior Lecturer at a top university in Australia . . . and he still enjoys going rock climbing.

In our modern world, overwhelm and distraction threaten to constantly derail us.

As artist Austin Kleon states in his book Keep Going:

“Your attention is one of the most valuable things you possess, which is why everyone wants to steal it from you. First you must protect it, and then you must point it in the right direction.”

In this article, I share a powerful practice that can help you protect your attention and point it in the right direction: working like a sprinter.

As a teenager, I remember watching Australian Aboriginal athlete Cathy Freeman run in the 400-metre race at the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

In that incredible race, Cathy did one thing and one thing only: she ran as fast as she could in a focused, intense burst.

She was 27 years old and had been training for this event for 17 years. Having won silver at the previous Olympics, the pressure was on. The entire nation was watching Cathy.

To this day, I still get goosebumps when I watch the footage of this race (you can watch it here).

Cathy was in the zone. She was completely focused on the task at hand. She knew what she needed to do: run.

Shortly after crossing the finish line, Cathy sat down to catch her breath and process what she had just accomplished (she had won gold). The crowd went wild and was completely absorbed in the moment, too.

Back in the year 2000, during the Sydney Olympics, smartphones and social media didn’t exist. Not everyone had access to the internet (my family did, but it was slow, expensive, and could only be used at home on a computer). In this environment, it was much easier to focus.

It’s fair to say that the early 2000s were simpler times.

Some scholars (e.g., Dr Jonathan Haidt, and Dr Anna Lembke) argue that smartphones and social media have caused several harms to society, including a reduced capacity to pay attention and an inability to tolerate discomfort.

Despite the noise and chaos of the modern world, it’s possible to train yourself to focus better.

How do we cultivate better focus?

One way is to tackle our work like sprinters.

The practice of working like a sprinter is refreshingly simple: You work in a short, focused burst (25-45 minutes), then take a break to rest and recover (5-15 minutes). After that, you repeat the process a few times before taking a much longer break (30 minutes).

I usually work this way for about 3 – 4 hours a day.

But I’m not fixed and rigid about this practice. This technique is adaptable. The key is to listen to your body and tune into what it needs. Make this practice work for you.

If you develop the habit of working in this focused way, you’ll be amazed by how much you can get done. More importantly, instead of feeling mentally fried at the end of the day, you’ll feel energised. You’ll also experience a delightful sense of calm and peace.

In short, this is a practice well worth cultivating.

In a nutshell, working like a sprinter involves three distinct phases:

It’s simple, but it’s a practice that takes practise.

Below, I delve into each phase in more detail and share some things that help me work in focused sprints.

I do my best work sprints in the morning between 9am and 12noon. But these focused sprints don’t just magically happen. It’s not like I roll out of bed and dive straight into a work sprint. First, I need to warm up.

The warm-up phase allows me to get in the right headspace and set up my environment to be focus-friendly. It has a dramatic impact on my brain’s performance, affecting my ability to focus, creativity, productivity, and mood.

Just to be clear, the stars don’t have to align, and the conditions don’t need to be perfect to kick off a work sprint. I’ve simply noticed that I can work better after engaging in a few behaviours and morning practices.

Here’s what I’ve found makes a difference . . .

What distracts you when you’re trying to work? What things frequently derail you?

Take note of the things that hijack your attention and throw you off track.

In one of my favourite books on getting organised, Organizing Solutions for People with ADHD, Susan Pinsky writes:

“The more you explore the distractions that keep you from working, as well as the tools that help you to focus, the more organized and productive you will become.”

Once you know what distracts you, you can figure out ways to deal with those distractions, which brings me to the next point . . .

For each distraction, think of ways to make it harder to engage with it. What barriers or strategies could you put in place? Are there any tools that could help you focus better?

For example:

Dealing with distractions from the outset (before you sit down to do your work sprints) makes it easier to stay focused and on track.

Many of us have become used to constant stimulation; without it, we feel anxious. This is why we reach for our phones and scroll through our feeds as soon as we experience a slight pang of boredom.

If you can relate to this, you will benefit from engaging in a daily meditation practice.

If you’re new to meditation, I recommend starting with the following tiny habit of doing a micro-meditation:

After I put on my shoes, I will pause and breathe in and out three times.

Not sure how to meditate? Close your eyes and focus on your breath, going in and out. If a random thought enters your mind (and it will), notice it and let it go. Then, return your focus to your breath.

Alternatively, you could listen to a guided meditation using an app such Insight Timer.

Clinical psychiatrist Dr John Ratey describes exercise as “like a little bit of Ritalin and a little bit of Prozac”. It’s powerful stuff.

Research shows that physical movement can help us focus better and learn faster. In terms of counteracting stress and boosting our mood, movement is like getting a biochemical massage.

This is one reason getting on my treadmill and doing interval training has become a non-negotiable part of my day. In the words of Tara Schuster:

“[Working out] is my preventative measure against the anxiety that lurks in my mind. I must throw myself out of bed in the morning and make it to the gym because I will always, always feel better for it.”

By warming up my body through physical movement, I’m able to warm up my brain by bathing it in feel good chemicals.

Deliberately exposing myself to the discomfort of running also helps me sit with the unpleasant feelings that arise when faced with difficult work. As Alex Soojung-Kim Pang states in his book Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less:

“Exposing yourself to predictable, incremental physical stressors in the gym or the playing field increases your capacity to be calm and clear headed in stressful real world situations.”

On the days when I skip my morning run or a weightlifting session, my wellbeing and productivity take a hit. I don’t feel as mentally sharp or confident about tackling my work. I’ve also noticed that I’m more likely to get distracted and give in to instant gratification during a work sprint.

Can you do anything in the evening to prepare for your morning work sprints? Completing a few quick tasks before bed can help you conserve energy the next day.

Here are a few simple things I like to do in the evening to get ready for the day ahead:

Doing these simple things allows me to carry out my morning routine with ease. Then, I can hit the ground running with a clear, focused mind for my first work sprint.

If I check my phone for messages and engage in frivolous texting first thing, I crave distraction and the dopamine hits that come with it for the rest of the day.

For these reasons, I have implemented the following tech rules:

This may sound extreme, but these restrictions are incredibly liberating. As the author of the book Stand Out of Our Light, James Williams states:

“Reason, relationships, racetracks, rules of games, sunglasses, walls of buildings, lines on a page: our lives are full of useful constraints to which we freely submit so that we can achieve otherwise unachievable ends.”

By blocking myself from digital distractions and all the noise that comes with it, I can focus on chipping away at the projects that are most important to me.

Just like a chef prepares all the ingredients before cooking a dish (i.e. they create the mise en place), set yourself up with everything you need to do your work. The last thing you want is to get a few minutes into a work sprint and realise you need to go find a pen that works.

If you have everything you need within arm’s reach, it’s easier to stay focused on the task and get into a flow state.

Once the warm-up phase is complete, we move into the sprint phase. Now, it’s time to do the work.

If you’ve done the work in the warm-up phase, the sprint phase is a lot easier. All you need to do is:

There’s no need to feel rushed as you work. You’re not competing with anyone else. This is not a race. It’s totally fine to take things slow.

Don’t expect the sprint phase to be pleasant. Even after a fabulous warm-up, you will most likely feel some discomfort and resistance about doing the work. This is normal.

You’ll feel the urge to run from this discomfort. But instead of running from it, befriend it. Remind yourself that the point of these work sprints is to move the needle on the things that really matter to you.

When the timer goes off, take a moment to acknowledge yourself for showing up to do the work. Remember, this practice takes practise, and you just got some reps in.

Now it’s time to rest. You’ll probably have some momentum by now, so you’ll feel like pushing on but stop what you’re doing and step away from your work. As Ali Abdaal mentions in his book Feel-Good Productivity:

“Rest breaks are not special treats. They are necessities.”

I’m not going to lie: this phase has been the hardest for me to master. As someone with workaholic tendencies, I’ve had to work hard at getting rest.

Why is the rest phase so important?

Because the longer you focus, the harder it is to maintain your focus. The act of focusing depletes your brainpower.

The best way to recharge a depleted brain is to rest.

Like focus, rest is a skill. It takes practise. You have to be able to resist the lure of busyness and our fast-paced, always-on culture.

Here are some of my favourite ways to rest and recharge at the moment:

Whenever I find myself wondering whether to keep working or take a break, I ask myself:

“What kind of boss do I want to be for myself? A mean-spirited, hard taskmaster? Or a generous, caring boss who looks out for their employees’ wellbeing?”

The answer is simple: I choose to be a generous boss to myself. Therefore, I give myself permission to rest.

I’ve come to see each of the phases of working like a sprinter (Warm-up, Sprint, and Rest and Recovery) as critical to staying healthy and balanced. Through trial and error, I’ve learned that skipping the warm-up or rest phase or going too hard in the sprint phase can lead to chaos and exhaustion.

As you cultivate the practice of working like a sprinter, significant things will happen to you. Not only will you notice that your productivity goes through the roof, but you’ll experience mental calm and clarity like never before.

As digital distractions no longer dominate your day, the noise of the world gets dialled down. You’ll find it easier to tune into what you need and what matters most to you.

I cannot stress enough that this is a practice that takes practise! One or two sprints won’t cut it. You need to persevere for long enough to experience the incredible benefits of this powerful practice.

Most of us do. We sit and stare at our screens or textbooks for large chunks of the day.

You’ve probably heard the phrase, “Sitting is the new smoking”. It sounds dramatic, but sitting for 30 minutes or more leads to:

• Reduced blood flow to the brain

• Increased blood pressure

• Increased blood sugar

• Reduced positive emotions

Even if you exercise at the gym, if you sit all day at work or school, that’s not good for you.

Most of us know we should move more and sit less, but knowledge doesn’t always translate into action.

I’ve known for years about the harms of sitting. Every year, I’d set a goal “To move more during the day”. But it wasn’t until this year that I finally got off my butt and started taking regular movement breaks. In this blog, I’ll share what made all the difference.

Part of my problem was telling myself to “move more” and “sit less”. This was way too vague for my brain.

When it comes to taking movement breaks, how long should we move for? How frequently? And at what intensity?

I recently came across a brilliant study, published in 2023, that answered some of these questions.

A team of researchers at Columbia University compared different doses of movement on several health measures (e.g., blood sugar, blood pressure, mood, cognitive performance, and energy levels).

The researchers were interested in exploring how often and for how long we need movement breaks to offset some of the harms of sitting for long periods.

So, what did they do in this study?

Researchers brought participants into the lab and made them sit in an ergonomic chair for 8 hours. Participants could only get up to take a movement break or go to the toilet.

They tested five conditions:

• Uninterrupted sedentary (control) condition (Note: no movement breaks)

• Light-intensity walking every 30 minutes for 1 minute

• Light-intensity walking every 30 minutes for 5 minutes

• Light-intensity walking every 60 minutes for 1 minute

• Light-intensity walking every 30 minutes for 5 minutes

The optimal amount of movement was five minutes every 30 minutes. This movement dose significantly reduced participants’ blood sugar and blood pressure and improved their mood and energy levels.

That said, even a low dose of movement (one minute of movement every 30 minutes) was found to be beneficial.

Although walking has been described as ‘gymnastics for the mind’ and numerous studies show brisk walking can improve cognitive performance, they found no significant improvements in participants’ cognitive performance in this particular study.

You can read the full study here.

When it comes to any research conducted in the lab, the question worth asking is: Is it possible for people to do this in the real world? And if so, will they experience similar benefits?

Journalist Manoush Zomorodi wanted to find out. So, she teamed up with Columbia University researchers to explore whether people could incorporate regular five-minute movement breaks into their day.

They created a two-week challenge where people could sign up to one of three groups:

1) Five-minute movement breaks every 30 minutes

2) Five-minute movement breaks every hour

3) Five-minute movement breaks every two hours

Over 23,000 people signed up to participate in the challenge. Sixty per cent completed the challenge.

What did they find?

Five-minute movement breaks improved people’s lives, whether taken every half hour, hour, or two hours. They felt less tired and experienced more positive emotions.

They found a dose-response relationship. This meant that the more frequently people moved, the more benefits they gained.

In the Body Electric podcast, Columbia University researcher Dr Keith Diaz said a preliminary analysis of the data showed:

• People who moved every 30 minutes improved their fatigue levels by 30%.

• People who moved every hour improved their fatigue levels by 25%.

• People who moved every 2 hours improved their fatigue levels by 20%.

Here’s the thing, though . . .

Dr Diaz pointed out that most people weren’t getting all their exercise breaks in. On average, they took eight movement breaks each day (note: the researchers recommended 16 movement breaks a day), but they still experienced benefits.

Here’s what I take from all of this . . .

You don’t have to do this perfectly. There are no hard and fast rules. Doing some movement is better than doing no movement.

All movement matters. It all adds up.

Although movement is natural and good for the mind and body, my brain often resists the thought of getting up and moving (“No! I don’t want to get out of this cosy chair!”).

What’s up with that?

In the book Move the Body, Heal the Mind, Dr Jennifer Heisz explains that our brains hate exercise for two reasons:

1) The brain doesn’t want to expend energy; and

2) Exercise can be stressful.

This has to do with how our brains are wired and our deep evolutionary programming.

If we go back in time, our hunter-gatherer ancestors had to be constantly on the move to gather food, build shelter and run from hungry animals. All of this activity required a lot of energy. Since food was scarce and energy was limited, hunter-gatherers had to conserve their energy.

If you were to offer a hunter-gatherer a free meal and a comfortable place to stay, would they take it? You bet they would.

The problem is our brains haven’t changed in thousands of years. We still have the same brain wiring as our ancient ancestors.

This is why my brain often throws a tantrum and comes up with all sorts of excuses to avoid my morning workout.

In this modern world, with all the calorie-dense fast food, comfy chairs, and modern conveniences, our brains get confused.

As evolutionary psychologist Dr Doug Lisle, author of The Pleasure Trap, states, in the modern world:

“What feels right is wrong. And what feels wrong is right.”

Understanding that we operate with an ancient brain that isn’t suited to this modern world opens up new possibilities. For example, you can use your prefrontal cortex (the rational part of your brain) to override the primitive instinct to stay comfortable.

Here are some strategies I’ve been experimenting with to get me taking regular five-minute movement breaks:

I’ve strategically placed electronic timers in every room I spend a lot of time in (e.g., my office, outdoor desk, and dining room). Before I sit down to start a task, I set a timer for 25 minutes.

When the timer goes off, that cues my brain to get up and move.

When the timer goes off, I usually jump on my treadmill for a five-minute walk. But not always.

Whenever I feel like doing something different, I play a little game with myself.

The game is simple:

I roll a dice with different movement activities I wrote on each side. Whatever activity it lands on, I do it.

Here are the activities currently listed on my dice:

• Pick up a set of dumbbells and do some bicep curls

• Do some stretches on my yoga matt

• Use resistance bands

• Go outside and walk around my garden

• Do squats

• Hit play on an upbeat track and dance!

Sometimes, the timer going off will not be enough to get you up and moving. You may need to have a few words with your brain.

I often find myself negotiating with my brain, trying to convince myself to get up and move.

Me: “Come on, it’s time to get up.”

Brain: “Noooo! It’s nice and comfy here.”

Me: “On the count of three, we’re going to do this . . . 1 . . . 2. . . 3.”

Be gentle with your brain. Remember, it’s wired for comfort.

There’s a reason I have stretch bands hanging on door knobs, a yoga mat rolled out on my dining room floor, a rack of dumbbells next to my desk, and comfortable walking shoes always on my feet. All of these little things make it easy for me to move.

Look around your workspace: is there anything that makes it hard for you to move? Identify any barriers and do what you can to remove them.

Instead of stopping to take a movement break, can movement become part of what you do?

For instance, I wrote the first draft of this blog as I walked at a slow pace on my treadmill desk, and I edited it while pedalling at my cycle desk.

Remember, movement doesn’t need to be strenuous to be effective. Light-intensity movement delivers results.

I recently finished reading an excellent book called Creative First Aid: The science and joy of creativity for mental health. It is packed full of creative practices to help calm your nervous system.

One of the practices the authors suggest is creating a playlist of songs called ‘I Dare You Not to Move’. This playlist is a selection of songs that make you want to dance.

On a movement break, I close my blinds and hit play on one of my favourite dance tracks.

Don’t consider yourself much of a dancer? No problem! Sway your hips from side to side or throw your hands in the air and make some circles with them.

Even though it may feel good in the moment to stay seated in a comfy chair, I have to regularly remind myself that movement makes me feel good (and less stiff and achy).

Remember, whenever we force ourselves to get up and move, we go against our brain’s programming. This is why these reminders are so important.

Before stepping onto the treadmill to do a run, I say to myself, “This is good for me. You won’t regret doing this”. And you know what? I always feel better after a workout.

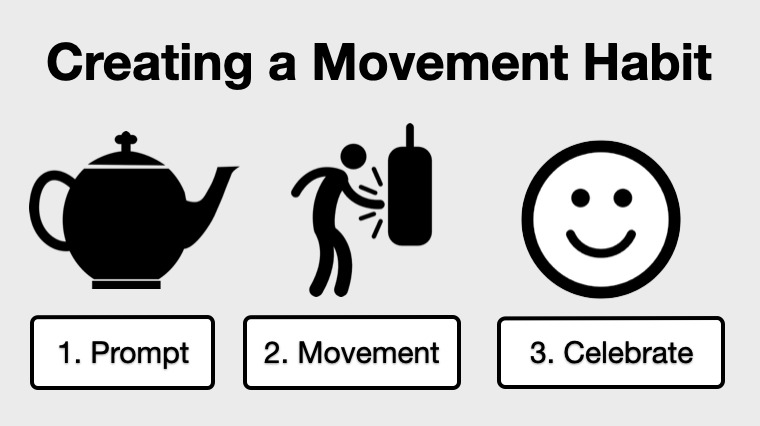

What is something you already do on a regular basis?

It could be making a cup of tea, preparing lunch, or putting on your shoes.

According to the Tiny Habits Method, the key to forming habits is to attach a tiny behaviour to a pre-existing habit. For example:

• After I put on the kettle, I will do five wall push-ups.

• After I shut down my computer, I will do arm circles for 30 seconds.

• After I put my lunch in the microwave, I will march on the spot.

• After I pick up the phone, I will stand up to walk and talk.

• After I notice I am feeling sluggish, I will hit play on an upbeat song.

If you want to wire in this new movement break quickly, celebrate after moving your body (i.e. release a positive emotion). I tell myself, “Good job Jane!”. But usually, the movement leaves me feeling good, so it’s not always necessary.

The science is in. We know breaking up periods of sitting with regular five-minute movement breaks can make a big difference to our mental and physical health. The good news is you don’t even have to break a sweat to experience these benefits (light-intensity movement will do the job).

If you can’t manage moving every half hour, no problem. Do what you can. Some movement is better than no movement. On that note, is it time to get up and move? Let’s do this together. How about a light walk? Or a short dance break?

On the count of three . . . one . . . two . . . three. Let’s go!

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive and engaging study skills sessions for Australian secondary schools. She has worked with thousands of secondary students, parents, teachers and lifelong learners over the past 15 years.

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to Dr Jane’s newsletter:

© 2025 Learning Fundamentals