Cramming can very easily become a bad habit. Let me explain.

When you procrastinate and leave your work until the night before it’s due, adrenaline and motivation kicks in. This allows you to work with crazy energy and intense focus.

At times, you might find yourself nervously thinking, “Can I get this thing done? Will I be able to pull this off?”. But you can’t afford to dwell on thoughts like these. There’s no time to waste! You have to stay focused, push forward, and keep pumping out your work.

And pump it out, you do!

Amazingly, in the early hours of the morning, you manage to pull it off. You reach the word count of your essay (“Woohoo! I did it! YES!”). And in that moment, you feel this incredible sense of relief wash away the intense pain, anxiety, and fear you felt for the last five or more hours. Your brain’s reward pathway lights up. Your brain gets flooded with feel good chemicals.

It’s this intense positive feeling that you experience straight after finishing an assignment that wires in the bad habit of last minute cramming. As Dr Barbara Oakley states in her book A Mind for Numbers:

“You can feel a sort of high when you’ve finished. Much as with gambling, this minor win can serve as a reward that prompts you to take a chance and procrastinate again. You may even start telling yourself that procrastination is an innate characteristic – a trait that is as much a part of you as your height or the color of your hair.”

When students manage to pull off a few all-nighters, they can start to delude themselves with thoughts such as, “This is just how I work. I work best under pressure” and “I do my best work (and only work) at the last minute”.

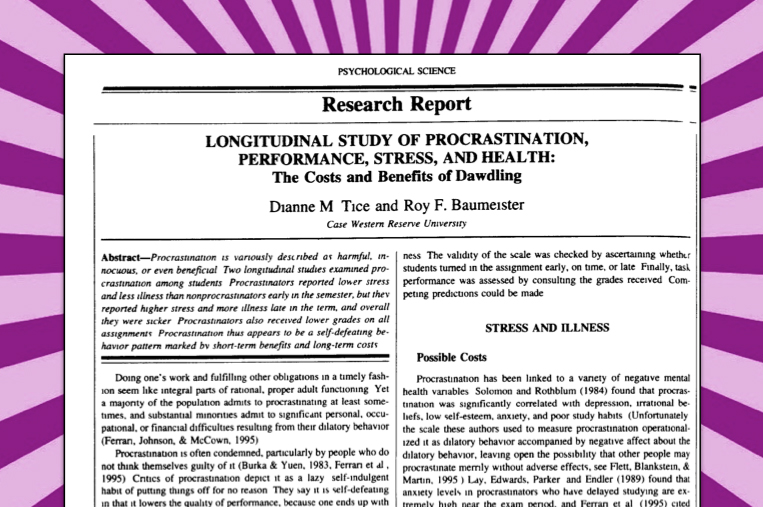

Studies show students who leave their work until the last minute don’t do as well as other students. They also tend to make more mistakes.

This study found procrastinators report higher stress levels, worse health, and lower grades.

When I first started university, I spent many late nights in the After Hours Computer Lab with my friends, crazily churning out essays the night before they were due. My friends and I were powered by bright fluorescent lights, sugary drinks, and snacks from the university vending machines.

At the time, it felt like fun. There was a sense of camaraderie in that computer lab. It was comforting to take a break when I hit a milestone (“Word Count: 1,000 words. Woohoo!”) and sink my teeth into a supersized chocolate chip cookie.

But looking back, that computer lab was a pretty depressing place to hang out. I can’t help but feel sorry for my younger self (Poor kid. What was I thinking?).

I can now see how the bad habit of cramming fuelled all these other bad habits at the time (e.g., bingeing on processed junk food and an erratic sleep routine). We were all suffering in that computer lab. We all needed help.

But when you’re stuck in that last minute, crazed, cramming habit loop you can’t see that you’ve got problems. You can’t see you’re heading for trouble. It’s the only way you know how to function and get stuff done.

It can feel hard for two reasons:

1) Procrastination delivers instant rewards (i.e., relief from the pain and discomfort of studying or writing a difficult essay). In contrast, the rewards that come from studying for an exam or working on an essay aren’t instant or guaranteed; and

2) The negative impacts of cramming don’t hit you straight away.

If after you reached the word count, you instantly felt really awful (e.g., mentally foggy, completely exhausted, and highly irritable) and all the mistakes and errors you had made flashed before your eyes, you would probably reconsider pulling all-nighters. You’d think to yourself, “This isn’t worth it. I feel terrible.” But it doesn’t work like that.

Like a bad hangover, that awful groggy feeling doesn’t hit you until several hours later. In relation to your grade and feedback, you don’t usually receive these until several weeks later. By then, you’ve forgotten how awful the cramming experience was.

Despite the negative impacts of cramming, some students tell me that they genuinely enjoy the challenge of cramming.

If this is you, I want you to think of cramming as being like an extreme sport, like Waterfall Kayaking, Skydiving and Barefoot Waterskiing. The sport of cramming requires a particular set of skills to pull off without seriously harming yourself. You’ll need to get better at:

• Managing your limited time and energy

• Managing your stress levels

• Memorising large amounts of material in a short period of time

• Keeping yourself awake for long periods of time (seriously not a good idea!)

I need to stress the following . . . going without sleep for long periods of time is incredibly dangerous.

In fact, this is why the Guinness World Records no longer accepts records for people going without sleep. This organisation will acknowledge records for people swallowing swords under water and pulling trains with their teeth, but not sleep deprivation records. That says a lot!

What about students who try to override their biological limits by taking medications like Ritalin (prescribed for attention deficit disorder) to get through cramming sessions?

Think twice about doing this.

As Dr Anna Lembke states in her book Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence:

“[These medications] promote short-term memory and attention, but there is little to no evidence for enhanced long-term complex cognition, improved scholarship, or higher grades.”

The good news is procrastination and cramming are habits. And habits can be changed.

This is the topic of my latest book Ace Tests, Exams, and Big Life Projects: How to End Last Minute Cramming, Reclaim Your Sleep, and Restore Your Sanity.

In my book, I explore why we often avoid preparing for exams. One reason we avoid exam preparation is because we’re scared. We fear the discomfort and pain it will bring up.

You see, we perceive exams as being like this creature . . .

A big jumbled, tangled mess of ideas (I call this creature the Beast of Overwhelm). We look at the creature (i.e., all the work we need to do) and it brings up a cringey discomfort. Since we don’t like feeling uncomfortable, we run from this creature. We run to anything that brings us instant gratification, comfort, and relief.

The problem is every time we do this we are moving further away from our long-term goals. Ultimately, when we procrastinate we are making life harder for our future selves.

You can start by making some tweaks to your environment. Redesign your study space to make it harder to escape from the beast. Create a focus friendly environment that allows you to hang out with the beast for a little longer.

For instance, set up barriers between you and the things that try to hijack your attention. Internet blocker apps, a Kitchen safe (Ksafe) for your phone, noise blocking earmuffs, and AdBlocker plugins can help you stay on track and move closer towards your goals.

Another strategy worth adopting is setting the bar really low. Try creating some tiny habit recipes.

The Tiny Habits method (created by Professor BJ Fogg) is the complete opposite of cramming. Tiny habits are behaviours that take less than 30 seconds to do. Unlike cramming (which can feel painful), tiny habits are fun, fast, and easy.

As Giovanni Dienstmann states in his book Mindful Self-Discipline:

“Don’t aim for perfect – aim for better than yesterday. Aim for 1% improvements every day. This compounds into huge results over time.”

This is certainly what I’ve found with using tiny habits. Tiny improvements add up over time to something really solid.

You can break the cramming habit once and for all. All it takes are a few strategies, a bit of understanding of basic psychology, and some practice. By creating better study habits, you’ll be amazed at what you can accomplish over time. You’ll also feel a whole lot better, too.

Share This:

But just to be clear – this car wasn’t in bad shape when I first got it. I turned this car into a jalopy through neglect and ignoring basic warning signs.

Whenever I gave my friends a lift in this car, I remember that they always looked visibly uncomfortable. They’d say with a nervous laugh:

“Jane, what’s that strange rattling sound?”

“Why is there a red warning light on your dashboard?”

I wasn’t fussed about the red light or the strange rattling sound.

Somehow, I’d missed the adulting lesson on basic car maintenance.

For many years, I never bothered to get my car serviced. I drove it to the point where it rattled and shook violently, the engine would cut out while driving, and the brakes squealed at a painfully high pitch.

It got to the point where I could no longer ignore these problems, but by then, it was too late. My car was beyond repair and could only be salvaged for scrap metal.

I’m embarrassed to share this, as that’s no way to treat a car that gets you from A to B and uses the Earth’s finite resources. But stay with me because there’s an important point I want to make, and it’s this. . .

When I was younger, I engaged in several unhealthy lifestyle practices. Whilst I never smoked, took drugs, or consumed alcohol, I ate huge amounts of processed junk food (I didn’t know how to cook).

I also frequently sacrificed sleep to pull all-nighters to complete my assignments (I struggled with procrastination).

In my first year of uni, I got up to some dangerous stuff. For example, when I was 18, I went to a party and hopped on a motorcycle with someone I’d only just met. The bloke then tried to impress me by doing a wheelie while I was on the back (i.e., driving with one wheel in the air)!

What can I say? I was young and incredibly naïve.

My body seemed resilient. It appeared capable of handling the shocks. But over time, I started feeling tired and rundown. Still, I kept pushing myself like my old car. The only time I could rest was when I got sick.

These days, everything’s quite different.

I am physically unable to thrash my body around like an old jalopy.

Something as simple as consuming too much salt or sugar can send my brain spiralling out of control.

I was reminded of this a couple of weeks ago when I visited a friend in hospital. Because I was spending a lot of time at the hospital, my usual routines of grocery shopping and cooking from scratch were disrupted.

But then to make matters worse, I was given $80 worth of vouchers to spend at the hospital cafeteria. I thought, “How bad can hospital cafeteria food be?”.

It turns out really bad.

Cheese kranskys (sausages), heaps of salty hot chips, deep-fried chicken, and soft drinks were the main options at this hospital cafeteria.

Unhealthy food seemed completely normalised in this hospital environment. My jaw dropped when I saw a patient order not just one but five cheese kransky sausages!

In this hospital setting, I also started to eat poorly. It was on my third day of eating hot chips from the hospital cafeteria when I noticed that these chips weren’t doing me any favours. I was feeling off my game.

So I decided enough was enough. I gave the remaining hospital food vouchers to a homeless man who was hanging around the cafeteria, desperate for a feed. It was back to home cooked meals for me!

This greasy processed hospital food had a ripple effect on the rest of my life. I slept badly, which impacted my ability to run the next morning (my joints hurt). I felt resistance to using my treadmill desk because everything felt much harder than usual. Since I was moving less, I was more distracted.

I know all this might sound a bit dramatic, especially to those of us who enjoy a few hot chips (e.g., my husband). Given my friend was in a hospital bed and couldn’t walk, I am fully aware of how lucky I am to be able to run in the first place (even with sore joints).

The point I’m trying to make is this . . .

I also know that small decisions, like eating too many hot chips or staying up late, can add up and take their toll on your mind and body. These tiny decisions can have a big impact on the way you feel.

When I was younger, I could eat whatever I wanted and still feel pretty good. Sometimes I’d feel a bit off, but not in a noticeable way.

As Dr Randy J Paterson states in his book How to Be Miserable in Your Twenties:

“In your twenties, some people can do practically anything to their bodies, experience no immediate physical consequences, and feel emotionally more or less well. Random sleep cycle, sedentary lifestyle, lousy diet, 90 percent of the day staring at screen, binge-drinking, isolation, the works. The body doesn’t completely fall apart, and the mind, while not thrilled, hangs on.

Later on, the effect is more immediate. Live exactly the same way at thirty-five, at forty-five, and things don’t go so well. Take a middle-aged car and drive it aggressively down jolting roads, loaded to the max, old oil clogging the engine, and it’s not going to last long. The baseline mood at forty-with no maintenance, no exercise, no dietary adjustment, no stability, and no social life- is misery. ”

Like a car, the human body requires regular basic maintenance. I see this basic maintenance as a collection of small behaviours that leave me feeling calm, grounded, and focused.

Here are a few things I need to do to keep myself running smoothly:

Every now and then, I’ll abandon these behaviours. I’ll have a day where I eat and do whatever I like. I’ll order takeaway, sit on the couch and binge-watch a series until late at night. I usually pay for it the next day, but it also gives me a better appreciation of these practices and what they do for my body and mind.

It’s all about tuning in and noticing how certain things make you feel. For example, when I was in my mid-20s, I noticed every time I ate deep-fried chicken, I experienced sharp stomach pains.

That was like the red warning light on my car dashboard going off in my body. But instead of ignoring it, I paid close attention. Eventually, I decided it wasn’t worth the pain. So I stopped buying greasy deep-fried chicken and eventually went plant-based.

There’s no doubt that modern life can be hectic and stressful. When you’re rushing from one thing to another, it’s easy to overlook the basics and ignore the warning signs.

I’m not proud of how I treated my first car, but I learnt from the experience. Now I make sure I get my car serviced regularly. This saves me time, money, and stress in the long run.

Similarly, it wouldn’t hurt to treat our bodies like a well-maintained vehicle, too. By dedicating time, energy, and attention to the small things that make us feel better, our experience of the present moment becomes richer. As longevity researcher Dan Buettner says, “You can add years to your life and life to your years”.

“Suzuki Swift 1.3 GTi 1990” by RL GNZLZ is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. (used in image 1)

“Scrap yard 22l3” by Snowmanradio at English Wikipedia (Original text: snowmanradio) is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. (used in image 2)

“Girl Rider” by DieselDemon is licensed under CC BY 2.0. (used in image 3)

“KFC Wicked Wings” by avlxyz is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. (used in image 6)

On these days, the temptation to procrastinate and distract oneself can be strong.

I recently spent a few days with my family in the countryside, where I enjoyed reading by a crackling fire. But when I found myself back home in my office, I struggled to get back into the swing of things.

I was experiencing a full-blown holiday comedown.

For some context, I had printed out the slides for an upcoming presentation that I needed to practise, but I felt resistance every time I looked at the slides.

My mind screamed, “Nooo! I don’t want to practise!”. Without even thinking, I kept pushing the slides away like a toddler smooshing their vegetables around on their plate.

But at some point, I caught myself in the act. Without berating myself, I managed to turn things around and ease into my practice.

In this blog, I’ll share a couple of simple strategies I use to get a better handle on my procrastination and overcome resistance.

According to Procrastination scholar Tim Pychyl, procrastination isn’t a time management issue. It’s an emotion management issue. If you can get a better handle on your emotions, you’ll have a better handle on procrastination.

Let’s unpack this…

Often, when we procrastinate, it’s because we’re trying to avoid experiencing negative emotions. The task we need to do brings up feelings of discomfort (e.g., boredom, fear, guilt, anxiety, and stress), so we avoid the task to make ourselves feel better.

But avoidance makes no sense when you think about it.

Oliver Burkeman explains the problems associated with avoidance in his book Meditations for Mortals. He writes:

“The more you organise your life around not addressing the things that make you anxious, the more likely they are to develop into serious problems – and even if they don’t, the longer you fail to confront them, the more unhappy time you spend being scared of what might be lurking in the places you don’t want to go. It’s ironic that this is known, in self-help circles, as ‘remaining in your comfort zone’, because there’s nothing comfortable about it. In fact, it entails accepting a constant background tug of discomfort – an undertow of worry that can sometimes feel useful or virtuous, though it isn’t – as the price you pay to avoid a more acute spike of anxiety.”

Dutch Zen Monk Paul Loomans labels the tasks we avoid as ‘gnawing rats’. He says these tasks “eat away at you under the surface”.

Have you noticed that whenever you try to avoid a task, it’s usually still on your mind, using up your precious mental resources?

That’s what Loomans means by the task eating away at you under the surface.

Why does he use the peculiar term ‘gnawing rat’? Looman’s daughter used to have pet rats that would eat loudly under his bed, keeping him awake at night.

Loomans explains that if you can befriend your gnawing rats, you can transform them into white sheep. Just like a white sheep follows you around passively, once you transform a task into a white sheep, it’s a lot easier to make a start.

The question is, how do you transform a ‘gnawing rat’ (a task you are avoiding) into a white sheep?

The key is to approach procrastination from a place of curiosity.

Loomans suggests creating a positive, open relationship with the task you’ve been avoiding. You need to sit with it or visualise the task. Instead of giving yourself a hard time, get curious about why you have such a strained relationship with this task.

Loomans advises:

“… you’re not being asked to immediately do whatever it is that’s gnawing at you. The assignment is only to establish a relationship with it. You let all the various facets sink in and then let them go again.

The rat no longer gnaws at you, and it has settled down. It’s no longer trying to get your attention, but follows quietly behind. It now has white legs and curly fleece – it’s turned into a white sheep.”

I decided to follow Looman’s advice with this presentation I had been avoiding. To begin with, I pulled out my slides and I just sat with them.

I closed my eyes, tuned into my body and asked myself:

“Why am I feeling resistance towards practising this presentation? What’s going on?”

Within 30 seconds, the answer came to me. The resistance came from how I thought I’d feel after doing my speech practice: exhausted and emotionally depleted.

You see, when I practice a presentation, I typically go into turbocharge mode. It’s like I’m delivering the real thing: I gesticulate, project my voice, pace around the room, and rely on my memory and the pictures on my slides to remember the content (I don’t refer to my notes).

All of this takes a lot of mental and physical effort.

So, naturally, when I looked at my slides for this one-hour presentation, I felt flat and heavy.

I equated one hour of presentation practice with having a fried brain by the end.

But then I had a brilliant idea. I thought, “What if this practice session didn’t have to feel like a hard slog? What if it could be fun, light and easy but still effective? What would that look like?”

It immediately occurred to me that I had to shorten my practice session, which brings me to the next strategy . . .

To keep my practice session fun, light and easy, I settled on doing just five minutes of speech practice.

Instead of pacing around my office and practising in turbocharge mode for an hour, I sat myself down with a hot chocolate. I set a timer for five minutes, pulled out a mini whiteboard and started recalling the content (scribbling out and drawing pictures of what I needed to say).

When the timer went off, I checked my notes to see how I went (What did I remember? What did I forget to say?).

Then, I checked in with myself – “How am I feeling after that mini practice session?”. Instead of feeling depleted, I was feeling good! I felt less overwhelmed by this presentation. The resistance had subsided. As Paul Loomans would say, the presentation had transformed from a gnawing rat into a white sheep!

I felt excited, even a little inspired.

I could have easily kept practising for another 10-20 minutes, but I decided to give myself a break to re-energise (I got up and walked on the treadmill for 2 minutes).

This gave me insight into the need to vary the intensity and mode of each study session, depending on my energy levels and what I have planned for the rest of the day. Sometimes it’s good to go into turbocharge mode, but not always.

Not every study/work session has to be hardcore. Work sessions that leave you feeling completely drained by the end can be counterproductive. As Professor BJ Fogg says, “Tiny is mighty”.

Firstly, tiny study sessions are less scary for your brain. Five minutes of speech practice and flashcard practice feels easy. You think, “I can do 5 minutes!”.

In contrast, one hour of study feels scary for your brain, which means you’re more likely to procrastinate.

When you go tiny, it’s also easier to give your full focus to the task at hand. Here’s the thing about focus: focusing your mind takes a lot of your brainpower. And you have a limited supply of brainpower!

As you sit there and study, your brainpower gets depleted. But research shows one way to boost your attentional resources (i.e. your brainpower) is by taking regular breaks. If you study in short focused bursts and then take a break, you can stay refreshed and ensure your study sessions are effective.

But most importantly, tiny study sessions help to create momentum, and they leave you feeling good!

I tend to push myself to the point of exhaustion when I practise my talks. But I can see now that this makes it hard for me to want to practise in the future.

By dedicating just 5–10 minutes to the task and enjoying it, I’m more likely to do another 5 minutes (or more) of practice tomorrow. Doing five minutes of practice every day is infinitely better than doing no practice or cramming a long practice session in the day before.

You’re not going to go from good to great in one tiny study session. But you can make meaningful progress and create the momentum you need to keep going.

So, don’t turn your nose up at five minutes of flashcard practice or 10 minutes of doing a practice test. If done with focus and intention, that’s a solid study session that can set you on the path to success.

Image credit:

Toddler (featured in image 2): “Skeptical” by quinn.anya is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Rat: “Fancy rat blaze” by AlexK100 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

While I always kept an eye on the amount of petrol in the tank, I also needed to pay close attention to my own personal energy levels.

It was important to avoid pushing myself past empty and depleting my energy reserves because if I did, I would end up feeling emotionally wrecked.

I clearly remember one day when I pushed myself too hard. Looking back, it seems comical now. But I wasn’t laughing at the time.

It was my 24th birthday. I had woken up that morning with great intentions, thinking “It’s my birthday! Let’s make it a great day!”

I was trying too hard to make it a “great day”. I was forcing it, and perhaps that’s partly why everything went pear-shaped. Here’s what happened . . .

I had a school presentation later that day, so I spent the morning preparing for it before driving over an hour to deliver the presentation.

The time slot for the talk wasn’t ideal—my talk was scheduled for the last period on a Friday afternoon—but I was thinking, “Hey! It’s my birthday. Let’s make it a great day!”

What can I say?

The session didn’t go well.

There were IT issues and the students’ minds were elsewhere. But you couldn’t blame the students. They were tired and I was the only thing standing between them and the weekend.

When I wrapped up the session, I felt tired and hungry.

But I foolishly ignored my body’s needs. On an empty stomach, I began the long drive home. I was desperate to get back and be in my own space.

Within 10 minutes, I found myself stuck in peak-hour traffic. But I wasn’t just stuck in traffic; I was also stuck in an anxiety loop.

Psychologist Risa Williams explains an anxiety loop as “a negative thought cycle that makes you feel stuck in a rut”. You can’t rationalise your way out of an anxiety loop. Logic doesn’t cut it.

I kept thinking about how the talk could have gone better, why my birthday had been such a flop . . . these annoying tunes kept playing over and over in my mind and they kept getting louder and louder.

I was about halfway home when something unexpected happened: I began sobbing uncontrollably behind the wheel of my car. I just felt incredibly sad.

I realised it was dangerous to drive while crying, so I pulled over and called my mum.

My mum and I would chat on the phone most days, but I remember this conversation especially well because my mum didn’t pull any punches.

Mum: What’s wrong Jane? Why are you upset?

Me: It’s my birthday and I wanted to have a great day but I just feel so awful. Everything has gone wrong today. The day has been a total flop.

Mum: Jane, have you had anything to eat?

Me: No.

Mum: You’re hungry! I know what you’re like when you’re hungry. You need to find a place to eat.

Me: But there’s nothing healthy to eat around here . . . there are no healthy options.

Mum: I don’t care. Order something. Anything. You need to eat. Go do that right now!

I found a café that was still open (it was 3:30pm) and ordered a burger from the menu.

When the burger came out 10 minutes later, I felt emotionally wrecked.

But after eating that big, juicy burger, I felt instantly better.

The world now felt like a new and different place. I had strength again. With tear-free eyes, a calm mind, and more energy in my system, I got in my car and drove myself home safely.

That experience taught me an important lesson. I learnt I had to stop pushing myself past the point of empty (something I’d done far too often for too many years).

I had to start listening to my body and the signals it was sending me.

Feeling hungry? Have a healthy snack.

Tired? Take a quick nap.

Thirsty? Have a few sips of water.

Sitting for too long and in pain? Get up and move.

Eyes and brain hurting from staring at a screen for too long? Take a break and look out the window.

It also taught me how engaging in small behaviours (tiny habits) can significantly impact how you think and feel.

All of these habits are designed to boost and conserve my energy. That’s the great thing about habits: they conserve your energy by automating your behaviour and combating decision fatigue. As Kevin Kelly states in his book Excellent Advice for Living:

“The purpose of a habit is to remove that action from self-negotiation. You no longer expend energy deciding whether to do it. You just do it.”

These 15 tiny habits are so deeply ingrained that I do all of them most days. I don’t waste time and energy thinking, “Should I go on the treadmill or stay in bed and read a book?” or “Do I do my gratitude practice or eat breakfast?” I have established a routine of healthy behaviours that work for me.

These tiny habits don’t take long to do, and best of all, they stop me from running out of energy and crashing. I also haven’t been sick in over three years (mainly due to Habit #13: Wearing a n95 mask).

You might be wondering why I’m still wearing a mask when covid restrictions have eased. There are a few reasons: I know several people with long covid (and they are suffering). Their quality of life is not what it once was.

I’ve also read a lot of the research on covid. Research shows covid can cause significant changes in brain structure and function.

This study found that people who had a mild covid infection showed cognitive decline equivalent to a three-point loss in IQ and reinfection resulted in an additional two-point loss in IQ.

Other studies have found covid can disrupt the blood brain barrier and cause inflammation of the brain. Since I rely on my brain to do everything, wearing a n95 mask (not a cloth or surgical mask) is a simple and effective habit I’m happy to keep up to protect my brain and body.

At the end of the day, cultivating healthy habits is about noticing the little (and big) things that make a difference and then experimenting with those things.

For example, Habit #3 (Moving on a treadmill first thing every morning) came about when I noticed the dramatic difference in how I felt on the days I ran on the treadmill compared to the days I didn’t (I felt mildly depressed on the days when I didn’t go for a run).

Habit #4 emerged after I noticed that eating a particular breakfast (overnight oats with berries) made me feel amazingly good compared to having a smoothie or a bowl of processed cereal for breakfast (which would spike my blood sugar levels).

Your health influences everything in life—and I mean absolutely everything. It influences how you interact with the people in your life, how well you learn and focus, your energy levels, and how you do your work.

As Robin Sharma explains in his book The Wealth Money Can’t Buy, health is a form of wealth.

Sharma writes:

“If you don’t feel good physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually, all the money, possessions and fame in the world mean nothing. Lose your wellness (which I pray you never will) and I promise you that you’ll spend the rest of your days trying to get it back.”

One way you can build your wealth is by cultivating tiny healthy habits.

As I think back to my younger self, 24 years old and ignoring the warning signs my body was sending me, I can’t help but feel a bit embarrassed. But as Kevin Kelly says, “If you are not embarrassed by your past self, you have probably not grown up”.

I’ve grown up a lot. I’ve come to realise developing awareness and taking time out to step back and reflect are critical to living a healthy, grounded life. When you notice what makes you feel good and not so good, you can make tiny tweaks to improve your life.

If you aim to do more of the things that leave you feeling good and less of the things that leave you feeling depleted and fatigued, you can’t really go wrong.

In the words of Psychologist Dr Faith Harper, “Keeping our brains healthy and holding centre is a radical act of self-care”.

On that note, take a moment to check in with your body. What does it need right now? Could you do something small to treat your body and mind with a little more care? Step away from the screen and do it now.

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive and engaging study skills sessions for Australian secondary schools. She has worked with thousands of secondary students, parents, teachers and lifelong learners over the past 15 years.

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to Dr Jane’s newsletter:

© 2025 Learning Fundamentals