On these days, the temptation to procrastinate and distract oneself can be strong.

I recently spent a few days with my family in the countryside, where I enjoyed reading by a crackling fire. But when I found myself back home in my office, I struggled to get back into the swing of things.

I was experiencing a full-blown holiday comedown.

For some context, I had printed out the slides for an upcoming presentation that I needed to practise, but I felt resistance every time I looked at the slides.

My mind screamed, “Nooo! I don’t want to practise!”. Without even thinking, I kept pushing the slides away like a toddler smooshing their vegetables around on their plate.

But at some point, I caught myself in the act. Without berating myself, I managed to turn things around and ease into my practice.

In this blog, I’ll share a couple of simple strategies I use to get a better handle on my procrastination and overcome resistance.

According to Procrastination scholar Tim Pychyl, procrastination isn’t a time management issue. It’s an emotion management issue. If you can get a better handle on your emotions, you’ll have a better handle on procrastination.

Let’s unpack this…

Often, when we procrastinate, it’s because we’re trying to avoid experiencing negative emotions. The task we need to do brings up feelings of discomfort (e.g., boredom, fear, guilt, anxiety, and stress), so we avoid the task to make ourselves feel better.

But avoidance makes no sense when you think about it.

Oliver Burkeman explains the problems associated with avoidance in his book Meditations for Mortals. He writes:

“The more you organise your life around not addressing the things that make you anxious, the more likely they are to develop into serious problems – and even if they don’t, the longer you fail to confront them, the more unhappy time you spend being scared of what might be lurking in the places you don’t want to go. It’s ironic that this is known, in self-help circles, as ‘remaining in your comfort zone’, because there’s nothing comfortable about it. In fact, it entails accepting a constant background tug of discomfort – an undertow of worry that can sometimes feel useful or virtuous, though it isn’t – as the price you pay to avoid a more acute spike of anxiety.”

Dutch Zen Monk Paul Loomans labels the tasks we avoid as ‘gnawing rats’. He says these tasks “eat away at you under the surface”.

Have you noticed that whenever you try to avoid a task, it’s usually still on your mind, using up your precious mental resources?

That’s what Loomans means by the task eating away at you under the surface.

Why does he use the peculiar term ‘gnawing rat’? Looman’s daughter used to have pet rats that would eat loudly under his bed, keeping him awake at night.

Loomans explains that if you can befriend your gnawing rats, you can transform them into white sheep. Just like a white sheep follows you around passively, once you transform a task into a white sheep, it’s a lot easier to make a start.

The question is, how do you transform a ‘gnawing rat’ (a task you are avoiding) into a white sheep?

The key is to approach procrastination from a place of curiosity.

Loomans suggests creating a positive, open relationship with the task you’ve been avoiding. You need to sit with it or visualise the task. Instead of giving yourself a hard time, get curious about why you have such a strained relationship with this task.

Loomans advises:

“… you’re not being asked to immediately do whatever it is that’s gnawing at you. The assignment is only to establish a relationship with it. You let all the various facets sink in and then let them go again.

The rat no longer gnaws at you, and it has settled down. It’s no longer trying to get your attention, but follows quietly behind. It now has white legs and curly fleece – it’s turned into a white sheep.”

I decided to follow Looman’s advice with this presentation I had been avoiding. To begin with, I pulled out my slides and I just sat with them.

I closed my eyes, tuned into my body and asked myself:

“Why am I feeling resistance towards practising this presentation? What’s going on?”

Within 30 seconds, the answer came to me. The resistance came from how I thought I’d feel after doing my speech practice: exhausted and emotionally depleted.

You see, when I practice a presentation, I typically go into turbocharge mode. It’s like I’m delivering the real thing: I gesticulate, project my voice, pace around the room, and rely on my memory and the pictures on my slides to remember the content (I don’t refer to my notes).

All of this takes a lot of mental and physical effort.

So, naturally, when I looked at my slides for this one-hour presentation, I felt flat and heavy.

I equated one hour of presentation practice with having a fried brain by the end.

But then I had a brilliant idea. I thought, “What if this practice session didn’t have to feel like a hard slog? What if it could be fun, light and easy but still effective? What would that look like?”

It immediately occurred to me that I had to shorten my practice session, which brings me to the next strategy . . .

To keep my practice session fun, light and easy, I settled on doing just five minutes of speech practice.

Instead of pacing around my office and practising in turbocharge mode for an hour, I sat myself down with a hot chocolate. I set a timer for five minutes, pulled out a mini whiteboard and started recalling the content (scribbling out and drawing pictures of what I needed to say).

When the timer went off, I checked my notes to see how I went (What did I remember? What did I forget to say?).

Then, I checked in with myself – “How am I feeling after that mini practice session?”. Instead of feeling depleted, I was feeling good! I felt less overwhelmed by this presentation. The resistance had subsided. As Paul Loomans would say, the presentation had transformed from a gnawing rat into a white sheep!

I felt excited, even a little inspired.

I could have easily kept practising for another 10-20 minutes, but I decided to give myself a break to re-energise (I got up and walked on the treadmill for 2 minutes).

This gave me insight into the need to vary the intensity and mode of each study session, depending on my energy levels and what I have planned for the rest of the day. Sometimes it’s good to go into turbocharge mode, but not always.

Not every study/work session has to be hardcore. Work sessions that leave you feeling completely drained by the end can be counterproductive. As Professor BJ Fogg says, “Tiny is mighty”.

Firstly, tiny study sessions are less scary for your brain. Five minutes of speech practice and flashcard practice feels easy. You think, “I can do 5 minutes!”.

In contrast, one hour of study feels scary for your brain, which means you’re more likely to procrastinate.

When you go tiny, it’s also easier to give your full focus to the task at hand. Here’s the thing about focus: focusing your mind takes a lot of your brainpower. And you have a limited supply of brainpower!

As you sit there and study, your brainpower gets depleted. But research shows one way to boost your attentional resources (i.e. your brainpower) is by taking regular breaks. If you study in short focused bursts and then take a break, you can stay refreshed and ensure your study sessions are effective.

But most importantly, tiny study sessions help to create momentum, and they leave you feeling good!

I tend to push myself to the point of exhaustion when I practise my talks. But I can see now that this makes it hard for me to want to practise in the future.

By dedicating just 5–10 minutes to the task and enjoying it, I’m more likely to do another 5 minutes (or more) of practice tomorrow. Doing five minutes of practice every day is infinitely better than doing no practice or cramming a long practice session in the day before.

You’re not going to go from good to great in one tiny study session. But you can make meaningful progress and create the momentum you need to keep going.

So, don’t turn your nose up at five minutes of flashcard practice or 10 minutes of doing a practice test. If done with focus and intention, that’s a solid study session that can set you on the path to success.

Image credit:

Toddler (featured in image 2): “Skeptical” by quinn.anya is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Rat: “Fancy rat blaze” by AlexK100 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Share This:

Procrastination feels heavy.

But what if we could turn combating procrastination into a fun game?

Lately, when I catch myself avoiding a task, I’ll play a little game to see if I can get myself to move in the right direction.

I’ve discovered that it’s best to approach any task with a curious and playful mindset. If you take yourself too seriously, all the joy and fun can get stripped from the process.

Often, when I play this game, I surprise myself because the strategy works! I’ll be off and running with a task I procrastinated on for days.

But sometimes a strategy won’t work. That’s okay. When this happens, I usually take a little break before trying another approach.

I don’t claim to be a grandmaster at playing the game of combating procrastination. But these days, I can catch myself when procrastinating, notice the warning signs, and get moving in the right direction.

In this blog, I share how you can combat procrastination in a fun and playful way to fulfil your intentions and accomplish your goals.

Are you ready to play?

Let’s begin!

If you want to play this game of combating procrastination, you first need to understand what procrastination is and the rules of the game.

I recommend you play this game on your own so you’re not competing against anyone else. There’s no first or second place, no runners-up, and no one wins a trophy.

You can play with others, but it’s a collaborative game where you cheer each other on and gently coach each other into action.

It’s also a game that never ends because the work never ends. You are constantly learning and growing.

In her book ‘Procrastination: What it is, why it’s a problem and what you can do about it’ Dr Fuschia Sirois defines procrastination as:

“ . . . a common self regulation problem involving the unnecessary and voluntary delay in the start or completion of important intended tasks despite the recognition that this delay may have negative consequences.”

In other words, procrastination is:

Delaying a task + you know you are causing your Future Self pain and suffering.

There are some simple rules you need to understand to combat procrastination. Once you cement these rules in your brain, life becomes easier. Instead of experiencing constant resistance, you discover ease and flow.

Difficult work tends to bring up unpleasant emotions, such as boredom, stress, anxiety, fear, and frustration.

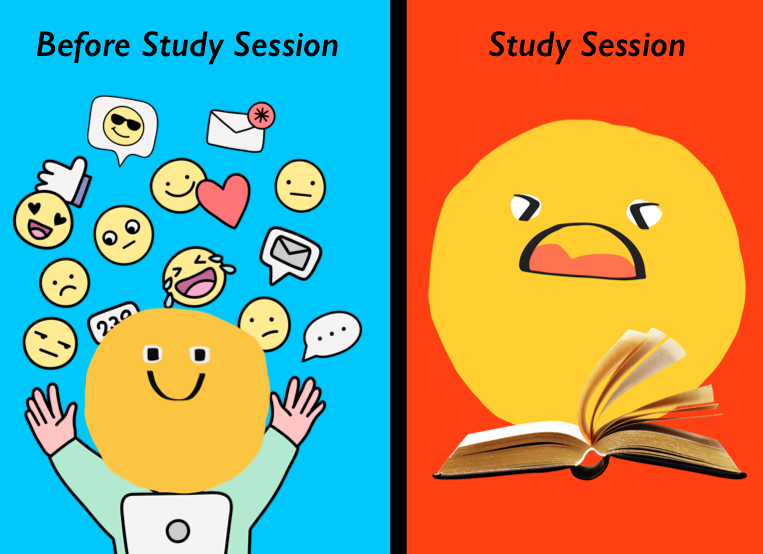

Most of us don’t like experiencing these feelings, so to repair our mood, we procrastinate. We avoid work and engage in easier, more fun tasks (e.g., scrolling through social media).

At the heart of combating procrastination is allowing yourself to sit with unpleasant feelings and push past them. Resist the urge to run to your devices. If you can do this, that’s 80% of the battle.

Pushing through the discomfort and making a start is a significant milestone worth celebrating.

Often, we wait for the perfect time to start a task. But it’s an illusion that there is a perfect time.

The perfect time is right now, amid the messiness and chaos of life.

“But I’m not feeling motivated!” I hear you say.

That’s okay. Make a start regardless of how you feel because here’s the part most people don’t understand:

Motivation follows action

In other words, you have to get moving for motivation to show up.

There are many great strategies and tools that can help you get started with a task, even when your motivation levels are low.

Once you have a selection of strategies and tools and you’ve practised using them a few times, you will feel more confident in your ability to combat procrastination.

Here are a few of my favourite strategies and tools for getting started with my work:

Fear is a significant driver of procrastination: fear that you won’t be able to do it, fear of failure, and fear of the unknown.

When you move your body, you decrease fear and anxiety. Movement can also help to calm and focus your mind and boost positive emotions.

This is why I start my day with a 20-30 minute run on my treadmill. It bathes my brain in feel-good chemicals, makes me feel stronger, and prepares me for the challenging work I’m about to face.

When a task feels big and overwhelming, it’s easy to procrastinate. But can you do 10 minutes on the task?

When I set a timer for 10 minutes, my brain thinks, “I can do 10 minutes. Easy!”

My brain then knows the task (and the unpleasant feelings) won’t last forever. The worst-case scenario is I experience 10 minutes of mild to moderate discomfort. When the timer goes off, I have a way out. I can do something else.

But what usually happens is after 10 minutes, I realise the task isn’t as bad as I thought it would be. The motivation has kicked in, and I’m on a roll.

When struggling to write my PhD, I attended a workshop led by an academic coach. She encouraged me to “Write crap” (her words, not mine).

This helped me to get over the perfection hump and make a start.

Most (if not all) great works started as rough drafts. The problem is we don’t see those rough early versions. We only see the polished final product. This messes with our minds and can lead to perfectionist tendencies kicking in.

Embrace the first messy draft. Celebrate it! You have to do it to get to the good stuff.

In the book ‘Everything in its Place’, Dan Charnas recommends the ‘Slow-but-don’t-stop’ technique for doing things you don’t want to do.

Here’s how it works:

If you’re feeling resistance towards a task, start doing it, but move very slowly. Breathe into the discomfort. Take your time.

Charnas writes that as you use this technique:

“You’ll still hate it [the task] but your task has become a moving meditation or like a game.”

For example, I used this strategy on the weekend to sort my laundry. The first step was to pick up the basket full of clothes and place it on my bed. Then, I picked up one item at a time and put them into piles (e.g., socks, activewear, and undies). I then selected a pile of items (socks) and dealt with one item at a time.

I’d usually rush to fold my clothes and feel slightly annoyed by the whole process (“Ugh, what a chore!”), but this time, it felt different. It felt like a meditation. I felt calm and grounded as I folded my socks.

The beauty of this technique is that the work will still get done, but as Charnas points out, you don’t give up control. You still have forward momentum.

As the Mexican proverb goes:

“An ant on the move does more than a dozing ox.”

Are there things in your workspace that distract you? Is there anything that reminds you of more fun stuff you could be doing (e.g., a video game console or your phone)?

Please get rid of those things or make them harder to access.

My phone is my biggest distraction. This is why I keep it away from my body in another room whenever I need to do focused work.

I’m currently experimenting with Mel Robbin’s 5-Second Rule. The 5-Second Rule is simple:

The moment you have the instinct to do a task before your brain can come up with an excuse not to do it, you count backwards ‘5 . . . 4 . . . 3 . . . 2 . . . 1!’ and you do it.

In her book ‘The 5 Second Rule’ Robbins explains the psychology underpinning the strategy. She writes:

“The counting distracts you from your excuses and focuses your mind on moving in a new direction. When you physically move instead of stopping to think, your physiology changes and your mind falls in line . . . the Rule is (in the language of habit research) a “starting ritual” that activates the prefrontal cortex, helping to change your behavior.”

The ultimate way to combat procrastination is to create a habit or a ritual. You need something that signals to your brain it’s time to engage in a particular behaviour.

With habits, you don’t have to stop and think, “What do I need to do now?”. Habits are automatic. Your brain knows exactly what it needs to do, and you do it.

For example, I have a habit of running on my treadmill before I launch into my day. My brain knows that after I put on my gym clothes and shoes, I turn on my treadmill and hit the speed button to start my warm-up.

I carry these behaviours out even when I’m not in the mood to run. That’s the power of habits.

Then, I suggest you cut yourself some slack.

Forgive yourself for procrastinating, pick a strategy, and get moving.

Most of us don’t do this, though.

We bag ourselves out in an attempt to motivate ourselves. The problem is this rarely works.

Dr Sirois says that intense self-criticism leads to negative thoughts, which lead to negative feelings. We end up feeling demotivated, which causes us to procrastinate even more!

You can stop the vicious cycle of procrastination by practising being kind to yourself.

If you follow these simple rules and be playful with experimenting with these strategies, you can get a better handle on procrastination.

Like anything in life, the key is practice. The more you practice allowing yourself to feel the unpleasant emotions instead of running from them, the better you’ll do. The more times you practice a strategy, the more natural it will feel and the sooner it will become a habit.

One foot in front of the other. You can do this.

About 10 years ago I met the beloved Australian celebrity Costa Georgiardis from the television show Gardening Australia.

I was blown away by Costa’s energy and enthusiasm.

He was exactly like he appeared on TV. But he wasn’t hamming it up for the camera. Costa was the real deal.

He was high on life.

I’ve heard that people often ask Costa “Why are you so energetic?”, “Why are you so up?”, and “Don’t you get tired?”

Some people feel tired just being around Costa (check out this video to get a sense of Costa’s energy).

What’s the difference between motivated and energised people and less motivated people who struggle to get off the couch?

According to Stanford professor Dr Andrew Huberman the difference has everything to do with dopamine.

In this blog post, I want to explore how dopamine works and how you can adjust your dopamine levels to experience more motivation, focus, and energy in a safe and healthy way. Let’s go!

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that is involved in reward processing. Your brain releases this molecule whenever it anticipates a reward.

In a healthy brain and environment, dopamine plays an important role in keeping you motivated, focused, and on track with your goals.

Unfortunately, this natural feedback system can be hijacked by big tech companies and fast food corporations.

Tonic dopamine is your baseline level of dopamine that circulates through your system. People who are generally enthusiastic and motivated have a high baseline dopamine. But if you struggle with motivation and often feel lethargic, chances are you have a low baseline dopamine.

But then there’s phasic dopamine. This is where you experience peaks in dopamine above your baseline level. These peaks occur as a result of engaging in certain behaviours and/or consuming certain substances.

For example, social media companies train users to seek out quick, easy, and frequent hits of dopamine. Fast food companies engineer foods that have just the right amount of salt, fat and/or sugar to release big spikes in dopamine. This make you want to eat more of the food product and keep going back for more.

It’s important to understand that these peaks in dopamine don’t last.

After engaging in a dopamine-rich activity, you will experience an inevitable drop in dopamine. And this drop will be below your baseline level.

It should come as no surprise that when you’re in a dopamine deficit state you don’t feel very good. You experience pain and discomfort.

According to Psychiatrist Dr Anna Lembke this is our brain’s way of trying to bring everything back into balance and establish homeostasis.

In the book Dopamine Nation Dr Lembke talks about how pleasure and pain are experienced in overlapping regions of the brain. She states:

“Pleasure and pain work like a balance”.

If you tip to the side of pleasure or pain, self regulatory mechanisms kick in to bring everything back into balance.

But you never want to tip to one side for too long. Dr Lembke states:

“With repeated exposure to the same or similar pleasure stimulus, the initial deviation to the side of pleasure gets weaker and shorter and the after-response to the side of pain gets stronger and longer, a process scientists call neuroadaptation . . . we need more of the drug of choice to get the same effect.”

In other words, consuming more of a dopamine-rich substance or behaviour is bad for your brain. It will leave you in a dopamine-deficit-state.

And when you’re in this state, it’s much harder to do your school work.

There are a number of simple things you can do to regenerate your dopamine receptors and increase your baseline dopamine. I’ve listed several strategies below.

Before you start your work or study, you want to avoid engaging in activities that will cause spikes in dopamine. If you watch TikTok videos or play video games before sitting down to do your homework, this is going to make your work feel a lot more painful and boring.

Here’s why . . .

Dr Huberman states that how motivated you feel to do a task depends on your current dopamine levels and what previous peaks in dopamine you have experienced. This is important to understand because with this knowledge, you can create routines and habits to conserve your dopamine and motivation for pursuing your goals.

With this in mind, I’ve recently simplified my morning routine in the following ways:

• I don’t start the day by looking at my phone or computer

• I exercise without listening to music

• I have a healthy breakfast of overnight oats and berries rather than a super sweet smoothie

• I have a cold shower (more on why I do this below)

Whilst this may sound boring, it’s had a dramatic impact on how easy it is for me to get stuck into doing my work.

The term ‘Dopamine Detox’ is a little misleading since it’s technically not possible to detox from dopamine. Nevertheless, the idea is a good one.

When you engage in a dopamine detox, you’re taking a break from engaging in dopamine-rich activities (e.g., consuming junk food, going on social media, and watching Netflix). This will give your dopamine receptors a chance to regenerate.

After taking a dopamine detox, you’ll probably notice that simple things like eating basic wholefoods or going for a walk are much more pleasurable. As Dr Huberman points out:

“Our perception for dopamine is heightened when our dopamine receptors haven’t seen much dopamine lately.”

Research shows that cold water therapy (i.e., being submerged in cold water) can increase your dopamine by 250% above your baseline level.

Let’s put that in context:

Chocolate increases dopamine by 150% above baseline

Alcohol increases dopamine by 200% above baseline

Nicotine increases dopamine by 225% above baseline

Cocaine increases dopamine by 350% above baseline

Amphetamines increases dopamine by 1100%

You need to remember that these peaks in dopamine are followed by a sudden crash below your baseline level. Let’s not overlook the fact that chronic substance abuse causes brain damage and can be fatal.

Unlike other addictive substances, cold showers create peaks in dopamine that can last for several hours. You also don’t experience the subsequent dramatic crash below your baseline level.

Word of warning: Before you turn on the cold shower tap or start running an ice-bath, it’s important to be aware that people can go into shock when plunging themselves into cold water. Please be careful!

If cold showers aren’t really your thing, try increasing your dopamine with exercise. Exercise has been found to increase dopamine by 130% above your baseline level.

In the book Move The Body, Heal The Mind, neuroscientist Dr Jennifer Heisz says:

“Exercise increases dopamine and repopulates dopamine receptors to help the brain heal faster during recovery [from addiction]. Although all forms of exercise can do this, runner’s high may do it best.”

Look for ways to make it harder to engage in the dopamine-rich activities. Create barriers and/or friction points to stop you from mindlessly seeking quick shots of dopamine.

For example, I recently noticed I had a problem with compulsively checking my phone. Whenever I felt bored or lonely, I’d check my phone to see if I’d received any messages. I didn’t like the fact I was doing this but I found it hard to stop. What could I do?

I could use a dumb phone.

I found a ‘seniors’ flip phone that allowed me to do basic things like make calls and send texts. But sending texts is not easy! I have to type in each letter and change from upper to lower case. It really puts you off wanting to text your friends.

Since switching to a dumb phone, the number of times I touch my phone each day has significantly decreased.

As you do your work, praise yourself for the effort you’re putting in. Doing this can increase the dopamine you have for the activity.

Dr Huberman suggests saying the following while you’re doing painful work:

“I know this is painful. But you need to keep at it. Because it’s painful, it’s going to increase my dopamine later and I’m doing this by choice.”

We live in a dopamine-rich world. It’s so easy to flood your brain with quick hits of dopamine that feel good in the moment but leave you feeling flat and irritable shortly after. These peaks in dopamine make it harder for us to pursue our goals by undermining our motivation.

No matter what your current dopamine baseline is, just remember this: you have the ability to increase your dopamine in a healthy and sustainable way. Kick-start the process today!

All of us have had the experience of watching videos instead of writing an essay. We can all relate to telling ourselves, “I’ll do it tomorrow”.

The problem is our brains are wired for comfort. We’ll try to do everything we can to avoid experiencing pain and discomfort. But through our avoidance behaviour, we ultimately create more pain and suffering for our Future Selves.

You can avoid working on a project, but eventually your Future Self will have to pay the price.

As Dr Benjamin Hardy states in his book Be Your Future Self Now:

“The more you put your Future Self in debt in terms of health, learning, finances, and time, the more painful and costly will be the eventual toll. There will be a lot of interest to pay if you continually accrue debt.”

This is why it really helps to cultivate habits and develop systems that help you get started with your work early (well before the deadline).

Over the last few months, I’ve come across several novel and effective ways people are combatting procrastination around the world. I write about each of these below.

The Manuscript Writing Café is a place where writers go to avoid distractions and meet their writing deadlines.

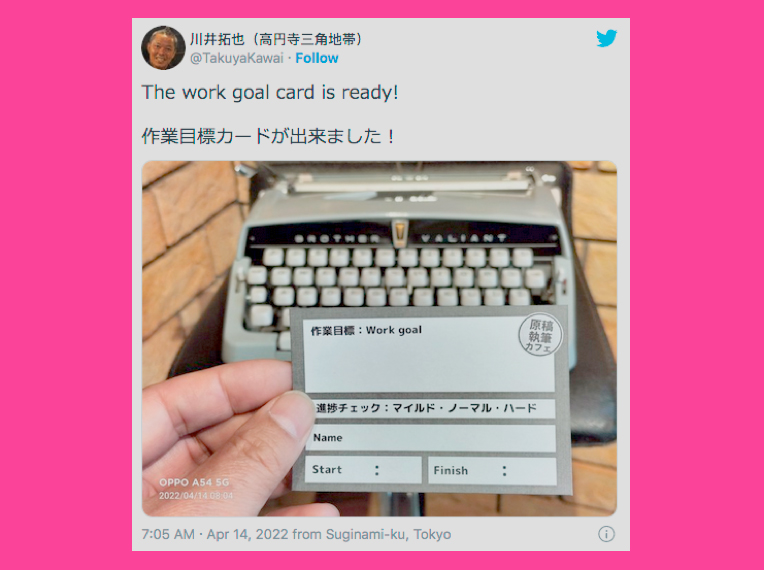

This is a disciplined environment where the owner Takuya Kawai won’t tolerate socialising over drinks. As Kawai states in a social media post:

“The Manuscript Writing Cafe only allows in people who have a writing deadline to face! It’s in order to maintain a level of focus and tense atmosphere at the cafe! Thank you for your understanding.”

In order for this café to run smoothly, Kawai has established a set of rules writers must follow upon entering.

Here’s how it works:

When you enter the café, you commit to a specific goal (how many words you want to write) and a time you plan on finishing. You write this down on a goal card.

You then select from three levels of progress checks:

1) Mild: You get a progress check at the time of payment

2) Normal: You get a progress check every hour

3) Hard: Staff frequently stand behind you and watch you working.

You can’t leave the café until you finish your writing goal.

Once you complete your writing goal, your goal card is stamped with a cute Japanese stamp and displayed on the wall with all the other completed goals.

Let’s unpack the psychology of how this clever café works . . .

Besides the fact you are working in a focus friendly environment away from all your usual distractions, it helps that you are in the company of other people who are also working towards clear goals.

When a staff member stands over your shoulder, you don’t want them to see you scrolling through social media or checking your email. You want them to look at you and think, “Oh wow! This person is super focused and on a roll. Look at them go!”

If you go to this café enough times and achieve a feeling of success after completing each writing goal, your identity will begin to shift. Instead of seeing yourself as someone who procrastinates, you start to see yourself as the sort of person who just gets on with doing the work.

It also costs money to be there. It is 130 yen ($1.30 AUD) for the first 30 minutes and then it increases to 300 yen ($3 AUD) per hour. Being charged a fee provides incentive to just get on with doing your work (procrastination equals parting with your hard earned money).

The owner insists his café is a supportive environment and his tactics are not heavy handed. He states:

“As a result, what they [the writers] thought would take a day was actually completed in three hours, or tasks that usually take three hours were done in one.”

You may not have an anti-procrastination café in your neighbourhood, but there’s nothing to stop you from setting up your own writing café experience and applying the same or similar rules.

This is what a group of PhD students and I did to help us write our theses (you can read more about this here).

This event is run by a number of universities around the world. Students are encouraged to come along with a work project they have been avoiding.

Educators, mental health nurses, therapy dogs, librarians, and academic coaches are on standby, ready to help students tackle their specific procrastination issues.

For instance, if a student is procrastinating with writing an essay because they don’t know how to write an academic essay, they can get help from an academic coach.

If a student is procrastinating because they get easily distracted, they can receive coaching on various strategies, such as the Pomodoro Technique, that will help them to deal with distractions and focus their mind.

When it comes to procrastination, there is no one size fits all approach. Nights Against Procrastination are popular and effective because they offer students a smorgasbord of different strategies and solutions to combat procrastination.

The Beeminder app is a commitment device/goal setting app that helps you stay on track with achieving your goals. Here’s how it works:

You commit to a goal (e.g., Read 70 pages per week). You set a daily target (e.g., 10 pages per day). If you get derailed from achieving your goal, you get stung with a charge from your credit card (you pledge the particular amount).

It sounds harsh but this app is your accountability buddy. There’s a real consequence associated with not engaging in the behaviour. This can give you the extra motivational boost you need to make a start.

The great thing about this app is it integrates with other apps and programs (e.g., Fitbit, Garmin, Duolingo, and RescueTime). Once you set up these integrations it’s a lot harder for you to weasel out of your goals. The data gets automatically imported into the Beeminder app and the data speaks for itself. You either achieved your daily goal or you didn’t.

If you’re going to use this app, you need to be really clear about your goals. And you need to be serious about achieving them because let’s face it, losing money hurts.

Cave Days are online focused work sprint sessions that take place on Zoom. You’re instructed to leave your camera on, put your phone away, close any unnecessary tabs, and work for 45 – 52 minutes. Before your work sprint session, you set a goal for what you want to accomplish.

These work sessions are facilitated by a ‘Trained Cave Guide’. The Cave Guide doesn’t tell you the exact time the session will go for because they don’t want you to be watching the clock the entire time. At the end of each work session, your Cave Guide will facilitate short break activities.

If you want to check this out, you can register for a free 7 day trial to see if this work method works for you.

There are many different ways you can combat procrastination. But be careful – searching for the perfect solution can become a form of procrastination!

The thing is there is no perfect solution. When it comes to doing difficult work, here’s what I find makes a difference: having your phone away from your body (preferably in another room), being clear on what you need to do, taking a deep breath, and getting started with a small task (even if you don’t feel like doing it).

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive and engaging study skills sessions for Australian secondary schools. She has worked with thousands of secondary students, parents, teachers and lifelong learners over the past 15 years.

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to Dr Jane’s newsletter:

© 2025 Learning Fundamentals