Research shows active recall (aka retrieval practice) is a highly effective strategy for remembering information. This strategy will take your studies and your grades to the next level.

Active recall involves bringing information to mind without looking at your books and notes.

I have spent the last 30 days experimenting with this excellent learning strategy. In this blog, I’ll share what I did and how I kept the process interesting for my brain.

I no longer need to study for tests and exams.

So, why did I spend 30 days using active recall strategies?

In my line of work, I need to constantly come up with new and original content to present to students. I also need to memorise this content. Why?

Because if I was to read from a sheet of notes or text heavy slides that would be really boring for students. I want to connect with students and to do this, I have to be able to deliver the content off the top of my head with speed and ease.

This is where active recall enters the picture.

Active recall helps to speed up the learning process. It allows you to learn more in less time.

Below I share some of the ways I use active recall to learn new presentation content. Keep in mind, you can use all of these strategies to prepare for an upcoming test or exam.

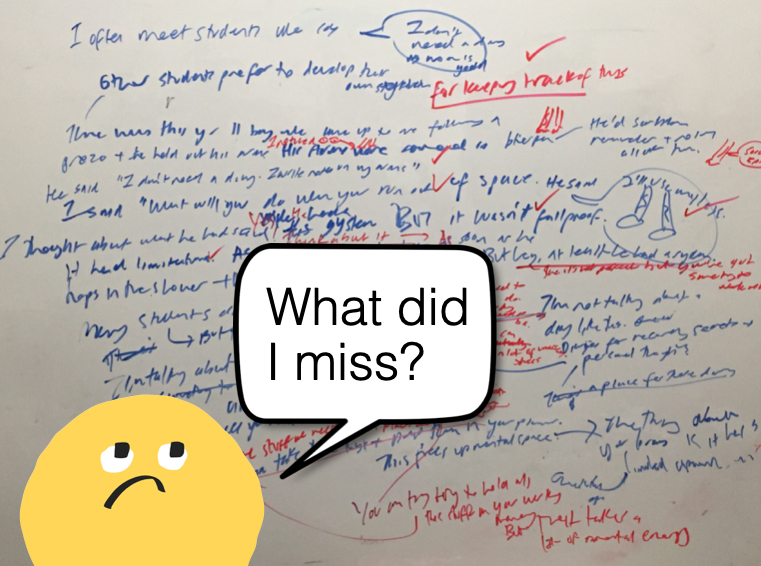

Whiteboards are wonderful learning tools. Here’s how I use a whiteboard to do active recall . . .

I push my speech notes to the side, so I can’t look at them. Then I grab a marker and say to myself, “What can you remember? Go!”.

I write out everything I can remember on the whiteboard. Once I’ve exhausted my memory, I pick up my notes and check to see how I went (using a red marker to make corrections).

No whiteboard? No problem!

I pick up a pen and sheet of paper and start scribbling out whatever I can remember on the topic. When I get stuck, I pause and take a few deep breaths as I try to scan my brain for the information.

I regularly remind myself that it is okay to not remember the content. “This is how the process goes!”, I say to myself. There is no point beating myself up. That only leads to feelings of misery and not wanting to do active recall practice.

After having a shot at it, I take out my notes, pick up a red pen, and begin the process of checking to see how I went.

Sick of writing? I get it.

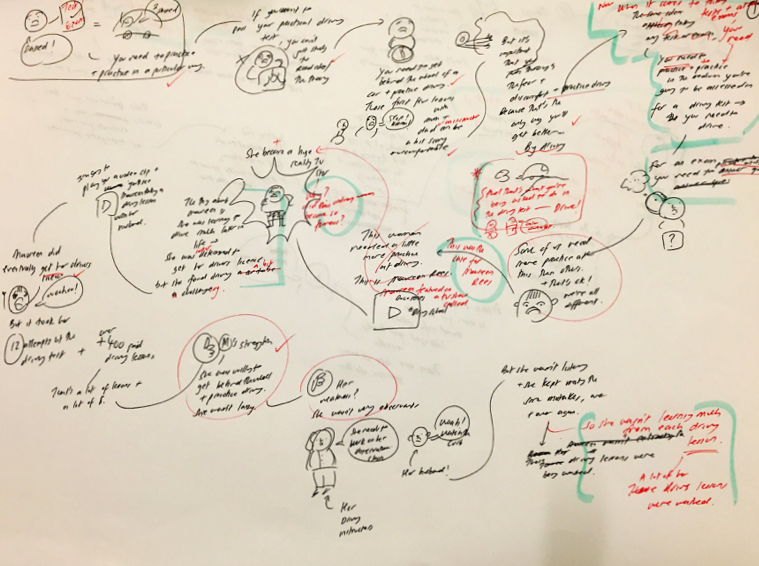

Try drawing out the information instead. Alternatively, you can use a combination of words and pictures, which is what I often do.

Grab a blank piece of paper (A3 size is best) and create a mind map of everything you can remember on a topic (no peeking at your notes). Then check your notes or the original mind map to see what you remembered correctly and incorrectly.

Writing and drawing out information can take time. If you want to speed up the process, you can talk to yourself.

But don’t do this in your head. It’s too easy to just say “Yeah, yeah, I know this stuff!”. You need to speak it out loud as this forces you to have a complete thought. Then, check your notes to see how you went.

The only downside with this approach is you don’t have a tangible record of what you recalled, which brings me to the next strategy . . .

I make videos of myself presenting the content (without referring to my notes). Although I use special software and tools to make my videos, you don’t need any fancy equipment. Your phone will do the job. Here’s what you can do . . .

Set your phone up so the camera is facing you. Now hit the record button and tell the camera what you’re going to do active recall on. Have a shot at explaining the idea. Then stop recording and hit the play button.

Watching yourself struggle to remember information is often hard viewing. But this is where it’s super important to double down on telling yourself kind thoughts (e.g., “I’m still learning this content. It’s going to be rusty and feel clunky – that’s okay!”).

You need to take a deep breath and keep watching because the video will give you valuable feedback.

For example, if you stop midsentence and you don’t know how to proceed, that tells you something: you don’t know this stuff so well! Make a note. This part of the content needs your attention.

Hand your notes over to a friend, parent, or sibling. Now get them to ask you questions on the content.

I sat with my mum and showed her a print out of my slides for a new presentation. The slides were just pictures (no text).

As I went through the slides, I explained the ideas to mum. I made notes of any sections I was rusty on. Mum also asked lots of questions, which allowed me to think more deeply about the content.

When it came crunch time (a few days before the final presentation), I printed out my presentation slides (16 per page) and used each slide as a prompt. I’d look at the slide and say, “What do I need to say here?”.

Sometimes I wrote out what I’d be saying in relation to each slide (without looking at my notes). Then I checked my original notes to make sure I hadn’t forgotten anything.

It’s really important that you don’t skip the stage of checking to see how you went, especially as you become more confident with the content.

At times, I found myself thinking “I know this stuff! I don’t need to check my notes” but then another part would say, “You better just check . . . just to be on the safe side”.

I’m glad I forced myself to check because more often than not I would discover that I had missed a crucial point.

Zines are cute little booklets you can create on any topic you like. They are fun to make, so I thought I’d try making a mini zine on the main points of some new content I had to learn.

I folded up an A4 page into a booklet and then I sketched out the main points on each panel.

I create a deck of flashcards on some key ideas (question on one side and the answer on the back) and then I test myself with them.

I read the question and before flipping the card, I write out the answer on a sheet of paper or say it out loud. Then I check to see how I went.

The beauty of flashcards is they are small and portable (they can easily fit in your pocket or bag). Whenever you have a spare minute or two, you can get a little active recall practice in.

It’s not enough to do active recall just once on the content you need to learn. For best results, you want to practice recalling the information several times over a period of time.

I didn’t follow a strict schedule for the 30 days. I had my notes for each important chunk of information I had to learn pinned to eight different clipboards.

Every morning, I’d pick up a different clipboard and I’d practice that specific content. I knew as long as I’d had a good night’s sleep in between practice sessions that the information was being strengthened in my brain.

Doing active recall is a bit like doing a high intensity workout: it can be exhausting. But you must remember, just like a high intensity exercise session is an effective way to train and get fit, active recall is an effective way to learn. Unlike less effective strategies (e.g., rereading and highlighting), you can learn a lot in a short space of time with active recall.

The key is to expect the process to be a little uncomfortable. Don’t fight the discomfort. If you trust the process and persevere, it won’t be long before you begin to see amazing results.

Just because active recall is challenging to do that doesn’t mean you can’t have fun with it.

Using a combination of different active recall strategies is one way to keep things fresh and interesting for your brain. But you may wish to try the following things to add a little boost of fun to your active recall sessions:

• Use a different type of pen

• Use a different coloured pen

• Change the type of paper or notebook you use (e.g., instead of using lined paper, use blank A3 paper)

• Incorporate movement into your active recall sessions (e.g., walk and test yourself with some flashcards)

• Change your study environment (e.g., go to the library or study outside)

Like I said, active recall is challenging to do, especially when you first start learning new content. You can feel awkward and clumsy. For this reason, it’s easy to make excuses to get out of doing it (e.g., “I’m too tired”, “I’m not ready to do it”, and “It’s not the right time”).

This is where you need to harness the power of habits.

Find a set time in your day to do a little active recall practice. For instance, during my 30 days of active recall, I scheduled my practice sessions for first thing in the morning. I knew after I washed my face, I would sit down to practice.

Incorporating active recall into my morning routine worked really well for me. I was getting the hardest thing done first thing in the day. And once it was done, I could relax. It was done and dusted!

At a certain point, I became more confident with the content and I found I was on a roll. I felt motivated to do active recall.

This is when I started to look for spare moments in the day to squeeze in a few extra mini practice sessions.

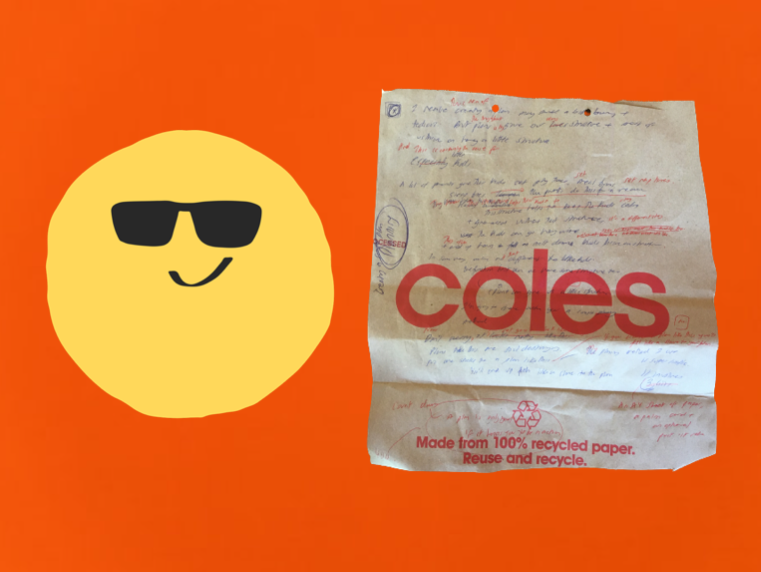

For example, one day I found myself waiting in a car. I grabbed a paper shopping bag and started scribbling out the content onto the bag. As soon as I got home, I checked the shopping bag against my notes.

I hope you can see that there’s no one set way to do active recall. This is a highly effective strategy you can be creative with. As long as you’re testing yourself and checking to see how you went, you can’t go wrong.

And if you do make a mistake? It’s no big deal. If you check to see how you went, you won’t embed the error in your long-term memory.

Share This:

But I’ve also had to learn to move to learn.

Does that makes sense? If not, let me explain myself.

Like most students, I was conditioned to sit still in a chair for hours each day. Even though I felt chained to my chair in school, there was one part of my body that I could move: my arms and hands.

I could gesture to express ideas.

Being half Italian, using my hands to gesticulate feels completely natural and normal. Growing up, I watched my Italian relatives gesture dramatically to stress a point and communicate ideas.

Having been exposed to this from a young age, I didn’t know how to behave any differently. It’s just what you did when you spoke: you used your hands.

However, my bold hand gestures weren’t always welcome, and they inevitably drew attention in the classroom.

People would comment, “Ha! Look at the way she uses her hands!” and “You’re so Italian!”.

My hand gestures were too over-the-top. I needed to tone things down.

When I was in Year 9, I tried to restrain my hand gestures. I alternated between sitting on my hands, folding them and cupping them in my lap.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but by suppressing my hands’ natural urge to move, I was doing my brain a disservice.

This study by Langhanns and Müller found that when students were asked to sit still while solving problems, their cognitive load increased and their overall success in solving problems decreased.

In other words, when you focus on being still and try to ignore your body’s natural urge to move, this consumes a lot of your brainpower.

Fortunately, I gave up trying to suppress my hand gestures. There was no point in trying. My hand gestures were like a wild horse. They would always break free.

All these years later, I can see that my ability to gesture naturally and effortlessly made me good at public speaking. While other robotic speakers had to be coached into adding a few hand gestures, I moved my hands with ease.

But that’s not all; by using my hands in class, I was also tapping into special learning superpowers.

Research shows physical movement, including the use of gestures, helps improve understanding and boosts memory.

I’m referring to an experimental study conducted by a husband and wife research team, Tony and Helga Noice. This couple spent many years studying actors and their ability to learn and recall lines.

Their research found that actors were able to accurately recall lines that had been accompanied by movements months after the final stage performance. However, these same actors struggled to remember lines that had been spoken when they remained in one place.

The Noices wanted to know if ordinary people (non-actors) could benefit from engaging in physical movement and using gestures when learning and retrieving dialogue.

They devised an experiment involving 23 university students. They split these students into three groups:

Group 1: Movement condition

Group 2: Verbal communication only condition

Group 3: Memorisation condition (Control)

In the movement condition, students were taught how to move in the scene (without reading their scripts). They were then given scripts and read their lines while moving their bodies.

In the verbal communication condition, these students sat on chairs and were told to read their lines out loud. They weren’t allowed to move.

Groups 1 and 2 were told not to memorise the dialogue but instead to focus on the meaning of what they were saying. They were instructed to adopt an actor’s approach to learning (i.e., to be fully present and mean what they were saying as they said it).

In contrast, Group 3 (the control group) was instructed to try to memorise their lines using whatever strategy they’d found successful in the past.

Students in each group were given only five minutes to learn their lines. They were then given a brief distractor task (“Write down five movies you saw recently”) before being tested on their ability to recall their lines.

The researchers found that the students in the movement condition remembered 76% of their lines compared with only 37% for the memorisation control group.

The researchers concluded:

“Students who actively experienced communicating the meaning of the material by using both words and movements recalled significantly more material than did either students who communicated using only words or students who deliberately memorized the same text.”

It’s important to note that the students in the movement condition weren’t just waving their arms around in the air. Their movements had meaning and were connected to what they were saying.

There are several ways you can utilise your body to learn.

If you’re trying to learn a new concept or memorise a presentation, don’t be afraid to use your hands and body. Think about what you’re saying. Can you apply a gesture or move your body to help you memorise an idea and improve your understanding?

As the authors of The Extended Mind In Action state:

“…the feel of our hands making a gesture reinforces our memory.”

This is why I also practice my presentations on my feet, using my hands and all my body to express ideas.

If you’re an online educator or teacher, it’s really important that students can see your arms and hands. Research shows that instructional videos that include people gesturing result in significantly more learning for people who watch them.

When I first started delivering online presentations, I made the mistake of only showing my head and shoulders.

After exploring the research in this area, I quickly adjusted my studio setup so that students could see my hands and arms as well. This small tweak made a huge difference in improving student learning.

I also encourage students to gesture back to check their understanding and reinforce key ideas. If you’re a teacher, I encourage you to try doing this with your students, too.

Besides using specific gestures and movements to learn concepts and dialogue, it’s also worth considering the benefits of engaging in light to moderate-intensity exercise before sitting down to study.

A fabulous research study called Sweat So You Don’t Forget found that when students engaged in five-minute exercise breaks every 17 minutes, they could focus better and remembered more than students who didn’t get any breaks or had a sedentary break (playing video games).

Annie Murphy Paul writes in her book The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain:

“…we have it within our power to induce in ourselves a state that is ideal for learning, creating, and engaging in other kinds of complex cognition: by exercising briskly just before we do so.”

This is why, every morning, before I start my work, I run on my treadmill or ride my stationary bike for at least 20 minutes. This gives me a cognitive boost: it improves my focus, creativity, executive function and ability to learn.

The movement also helps to decrease anxiety by supplying my brain with a dose of BDNF (i.e. brain-derived neutrophic factor). Dr Jennifer Heisz, in her book Move the Body, Heal the Mind, explains that BDNF is like fertiliser for the brain. She writes:

“BDNF acts like a fertilizer that promotes the growth, function, and survival of brain cells, including those that turn off the stress response.”

She continues:

“Immediately after exercising, our brain cells are bathed in BDNF, which protects those cells against the toxic effects of high stress.”

As I think back to high stress times in my life, I have no doubt that movement (and regular doses of BDNF) are what got me through these periods.

Your body is a powerful tool to help you learn. The research is clear that moving your body enhances your ability to think and learn.

It’s time to move past the outdated idea that learning means sitting still and being serious. It costs us nothing to gesture with our hands while reading about a concept or to go for a walk outside before studying.

Movement benefits us in many ways, so why not include some in your study routine today?

This usually comes with shiny new pens, fresh notebooks and renewed hope and optimism. But I recently heard someone say:

“I can’t believe it’s already the end of January . . . so much has happened. I feel tired.”

Can you relate?

A lot has been happening in the world. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the news, let alone the tsunami of information we’re bombarded with online.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed and tired (like many people are), let’s try to make life a little easier for ourselves. In this article, I share a strategy you can use to make difficult things feel easier to do. I also share how you can apply the strategy to studying challenging subjects.

I remember having a brief conversation with a year 11 student at the start of the pandemic. It went something like this . . .

Me: How are you feeling given the situation (i.e., COVID-19)?

Year 11 Student: Some of us are stressed but not because of COVID. It’s because of what our teachers have just said to us.

Me: What have your teachers been saying to you?

Year 11 Student: They keep saying this year is going to be really hard. The subjects are going to be much, much harder.

Driving home from the talk, I couldn’t stop thinking about what this student had said as well as the worried look in her eyes.

Here’s what happened . . .

I was booked to deliver a presentation to 150 year 10 students. My talk was scheduled for the last period of the school day.

In case you’re not aware, the last period of the school day is not an ideal time slot for a guest speaker. It’s usually a tough gig, as students are tired and they just want to go home.

When I arrived at the venue to set up my gear, I spotted two teachers. I approached them and introduced myself to them as the guest presenter. One of them said in an alarmed, panicky tone:

“Oh! You’re the guest speaker? I need to warn you that these students are a horrible group. They do not warm to guest speakers!”

She continued. . .

“Does your talk have a structure to it? Do you know what you’re talking about? These year 10s are a really hard group to work with!”

I felt my stress levels begin to rise, and by accident, I knocked my glass of water off the stage, and it broke. Glass shattered everywhere. Instead of helping me pick up the glass, the teacher said:

“Look! It’s a sign of things to come!”

At this point, the young IT guy arrived to help connect my laptop to the AV system. He overheard this teacher talking about what a bunch of ratbags these students were. His expression was a combination of shock and horror. He said to her:

“Why are you saying this to our guest presenter? I don’t think it’s helpful.”

The teacher reacted defensively. She blurted out, “She needs to know! It’s important we tell her!” and then she left in a hurry.

I took some deep breaths and continued setting up my stuff.

The students arrived.

I delivered the talk.

The talk went really well. Phew!

It turns out these students weren’t horrible at all. They were a normal group of students who happened to be a bit tired and over it (it didn’t help that it was a boiling hot day).

That day, I learnt an important lesson: Worrying about how difficult something might be doesn’t help. It just uses up your precious brainpower and energy, which you could have spent doing something else (i.e., something more productive).

Whenever I fixate on how hard something will be, I’m filled with fear. Imposter syndrome and self doubt kick in (“Will I be able to do this? What if I fail and it turns out to be a total flop?”). This usually leads to a bad case of avoidance and procrastination.

In the book Make It Stick, Peter Brown explains:

“A fear of failure can poison learning by creating aversions to the kinds of experimentation and risk taking that characterize striving, or by diminishing performance under pressure, as in a test setting.”

If you feel worried that you’re not going to be able to perform well in a subject, this is going to use up a big part of your working memory capacity. Instead of thinking about the content, you’ll be thinking, “Am I going to be able to do this? What if I can’t? Should I drop the subject?”.

In short, you’ll have dramatically less brainpower available for learning.

There’s a simple question I ask myself when something feels hard. And it’s this . . .

How can I make this behaviour easier to do?

Professor BJ Fogg calls this the Breakthrough Question. According to Fogg, there are three ways you can make any behaviour easier to do:

In his book Tiny Habits, Fogg explains:

“Regardless of what your aspiration is, increasing your skills, getting tools and resources, and making the behaviour tiny are what makes things easier to do. . .

Sometimes all you’ll need is the right tool to make a new habit easier to do, like using skinny floss [for flossing teeth], and other times all you have to do is scale the behaviour back to its tiniest version, such as flossing just one tooth. Think of making something easy to do as a pond with three different ways to enter the water. Whether you jump off the dock, wade in at the beach, or drop in from a rope swing, you’ll soon be swimming in the same water.”

In other words, you have options!

There are many things you can do to make studying those ‘hard’ subjects a little easier.

With that in mind, here is a short list of behaviours and ideas that will help you get a better handle on your challenging subjects:

If you can focus better, you can learn and retain more information. If you constantly check your phone, put it on silent and away from your body before you sit down to study. My phone lives in pocket number 1 of a vertical wall hangar in my dining room (well away from my workspace).

Study strategies such as active recall (e.g., flashcards) and dual coding (e.g., mind mapping) are more effective than rereading and highlighting your notes. Like any new skill, they take a little time to get used to, but they’ll save you a lot of time in the long run.

Some textbooks explain ideas better than others. The textbook on your school booklist is not the only one or necessarily the best one out there. You don’t need to feel wedded to it. Check out other study guides and resources.

A good night’s sleep allows you to focus better in class, retain more information and feel better. Make sleep your top priority. Here are some behaviours I engage in to get more and better sleep:

In the evening, I put my phone away in another room to charge (and I don’t touch it until the next day)

I don’t look at any screens at least one hour before bed

I go to bed at the same time and wake up at the same time everyday

Create a system to organise your notes, past exam papers and handout sheets. Over time, you may need to tweak and refine your system, but that’s okay. I’ve been tweaking and refining my system for years.

For example, I used to store all my mind maps in an A3 flip file (in no particular order). But when things started to get out of control, I switched to cataloguing them alphabetically.

If you’re confused, don’t suffer in silence. Ask your teacher for help. That’s their job. If you feel shy asking a question in front of the class, approach your teacher after class.

Make life easier for your future self by jotting down key ideas in class. If something is confusing, make a note (you can focus on that in a study session at home). Your memory has limits, and if you don’t write it down, chances are you won’t be able to remember it.

If you feel overwhelmed by the idea of doing several hours of study each day, start with just five minutes. Five minutes of study is infinitely better than doing nothing!

Once you’ve developed the habit of sitting down and studying for 5 minutes, you can ramp it up. But start small.

When you manage to sit down and do a little study, congratulate yourself. Say to yourself, “Good job!” This positive reinforcement makes us feel good, which helps us establish a study habit.

When your teachers say, “This subject is going to be really hard”, I think they’re trying to communicate to you, “You need to sit down and study. You can no longer wing it.” They may be afraid that you’re not taking things seriously.

Instead of worrying, be in action. Pick up some flashcards and start testing yourself. Tidy your desk. File away your notes from today. You’ll feel better and do better if you focus on doing the things that make studying that subject a little bit easier.

You need to practice. And practice in a particular way.

If you’re preparing for a driving test, you can’t just study the Drive Safe Handbook (i.e., the theory and road rules).

You need to get behind the wheel of a car and drive.

Yes, it can feel uncomfortable and scary to begin with. But you’ll only improve your driving skills by pushing through the discomfort, placing your hands on the wheel and your foot on the accelerator.

If a person spent all their time only studying the road rules and never getting behind the wheel of a car, how would they go in the driving test?

It would be disastrous!

Yet, many students are approaching exams in a similar way.

These students are doing the equivalent of only studying the road rules handbook before the exam.

Here’s how they prepare for academic exams:

• By creating beautiful sets of notes

• By rereading their books and notes

• By highlighting their books and notes

• By rewriting their notes

• By summarising their notes

These are not effective ways to prepare for an exam.

Do these ways of revising feel nice and easy?

Yes. They certainly do.

But are they effective ways to remember information?

No.

Think about it like this . . .

What do you need to do in most academic tests and exams?

You have to read questions and pull the information out of your brain. Most of the time, you can’t look at your notes and books.

It’s just you and your brain.

You’re not being assessed on your ability to summarise information, your ability to reread your notes, or highlight information. So, why would you prepare for an exam in that way?

The best way to prepare for an exam is by practising remembering information. This is how you become masterful at answering questions with accuracy, speed, and confidence.

You don’t get that speed, confidence, and deep understanding by rereading your books and notes.

If you reread as an exam revision strategy, the only confidence you develop is fool’s confidence. You delude yourself into thinking you know it (“I’m ready!”). After reading your notes a few times, the ideas feel familiar to you (“I know this stuff”).

But trust me, you’ll struggle to retrieve the information in the exam.

Imagine yourself driving through red lights and failing to take the handbrake off before you leave the parking lot: that’s you . . . and it’s a fail.

I know this may sound harsh. But I’m speaking from personal experience.

In high school, it felt good to highlight my notes and reread them leading up to an exam. However, when it came crunch time, I was stressed out in the exam because I couldn’t retrieve the information. I felt embarrassed and confused by my results.

“But I studied so hard!” I’d cry. Why didn’t all those of hours of reading translate to better grades?

I wish someone had gently explained to me, “Yes, you did study hard. But you didn’t study effectively”.

Fast forward 20 years and I’ve learnt how to study smarter (not harder).

“The best way to prepare for any test or exam is to use a learning technique called active recall.

Active recall involves testing yourself.

You push your notes and books to the side and try to bring to mind as much as you can about a topic you’ve already covered in class. For example, you can use a piece of paper to write or draw out what you can remember on the topic. Once you’ve exhausted your memory, you check your books and notes to see how you went.

Yes, this is challenging. But it delivers results.”

I use this technique to learn content for all my school presentations.

When I speak to a group of students, parents, or teachers, it may look like I’m casually explaining strategies, but all my presentations are carefully planned and practised.

If I didn’t do this critical prep work, I would end up rambling.

This is why two weeks ago, I started doing active recall to learn a new presentation —or at least, I thought I was doing active recall.

I pulled out a copy of my presentation slides that had my notes scribbled all over them.

Within the first five minutes, I had to stop and be honest with myself: I wasn’t doing active recall. I was reading my notes.

Many of us can fall into the trap of rereading when doing active recall.

As the Learning Scientists state in their book Ace That Test:

“When you try to bring information to mind from memory, it often feels really difficult. It can be really tempting to quit or try to look up all of the information in your notes or your textbook, but slipping into re-reading your notes or textbook will reduce learning. Instead, it is better to try to bring as much information to mind from your memory as you can, and only after you have tried this should you look in your notes, textbook, or other course materials to see what you got right and what you forgot or need to work on more.”

Reading your notes/books over and over again feels nice and easy. It doesn’t require a lot of strain and mental effort.

In contrast, active recall can make us feel clumsy and awkward, especially in the early stages of learning something new.

So, I asked myself the question:

How can I stop myself from rereading when I do active recall?

I brainstormed ideas and devised a plan. Then, I broke down the process and practised running through it several times. To my delight, it worked!

Whether you’re trying to learn a new presentation or preparing for an academic test or exam, here is a process you can follow to avoid the trap of rereading.

Clear away your notes, books, and any other distractions. Let’s face it: if your notes and phone are in front of you, it’s like having a packet of crisps or a bowl of lollies within arms’ reach. It’s too tempting.

Your notes are important (you need them for step 4), but for now, take them and place them away from your body in another room.

Active recall requires 100% of your brainpower. If your attention shifts from your study to your phone, the effectiveness of your active recall sessions decreases. This is why I highly recommend you put your phone away from your body in another room before you sit down to do active recall.

Once you’ve cleared away distractions, take out your practice exam paper or list of questions (in my case, a printout of my presentation slides) and get a pen, a timer, and some sticky notes.

Your goal for the next 10 minutes is to recall as much as possible. Exhaust your memory.

I scribble all over my slides (yes, it’s a messy process). If I run out of space on the page, I grab a sticky note, write the additional information on it, and then stick it down on the relevant slide.

During these 10 minutes, expect to experience some discomfort. In fact, welcome and celebrate the discomfort!

The discomfort is a sign that you are on the right track and deep learning is happening.

Active recall can be mentally exhausting. After doing 10 minutes, reward yourself by taking a quick break. I usually get up and move my body. Sometimes, I make myself a warm drink or smoothie.

Before returning to your workstation, grab your notes or the answer sheet from the other room.

It’s not enough to pull the information out of your brain. You have to see how you did (what you got right and wrong and where the gaps in your knowledge are).

So, how did you go?

At this point, enter teacher mode. Pretend to be a teacher giving yourself feedback.

I pull out my red gel pen, fun stamp and sticker collection, and highlighters.

Now is when it’s okay to look at your books and notes. Pull them out and begin marking up what you got right, wrong and anything important you missed.

In my case, if any presentation content is a bit rusty, I’ll highlight that section. The highlighter signals to my brain that this section needs extra practice.

It’s important to celebrate any content you recall correctly. Give yourself a tick, a fun stamp or sticker or draw a smiley face to congratulate yourself.

This is a process. It usually takes a few practice sessions to successfully retrieve the correct information. Encouraging yourself makes the process fun and gives you a feeling of success (“I’m making progress!”).

Once you finish step 4, make a note for your future self: what question or section will you work on for your next active recall session?

This reduces decision fatigue. When you next sit down to study this subject, there’s no need to waste precious mental energy thinking, “What should I revise next?” Your brain knows exactly what it needs to do, and you can begin doing active recall straightaway.

After you’ve decided on your starting point, prepare your workstation for your next active recall session (e.g., put your notes out of sight).

These six steps work for me. But feel free to modify this process so it works for you. For example, it can help to do active recall with others (e.g., in a study group with friends testing each other). When everyone experiences the discomfort together, the process becomes less painful and more enjoyable.

Active recall works, but paradoxically, it feels like it’s not working. Often, when I do active recall nothing comes to mind. That’s normal! Don’t use this as an excuse to abandon this highly effective strategy and return to rereading, which is an ineffective strategy.

My advice is to trust the process. You need to persevere with this strategy for long enough to see with your own eyes that it works. Don’t expect instant results. This process takes time, but the results are well worth it.

Dr Jane Genovese delivers interactive and engaging study skills sessions for Australian secondary schools. She has worked with thousands of secondary students, parents, teachers and lifelong learners over the past 15 years.

Get FREE study and life strategies by signing up to Dr Jane’s newsletter:

© 2025 Learning Fundamentals